When we select a frame for a painting, or adorn a store’s entrance with a neon sign, it’s like stopping the clock — preserving the memory of our best moments as vividly as possible. A considerately-framed artwork allows its viewers to picture the emotions the artist went through during its creation, while a neon sign illuminates its surroundings and evokes the halcyon days of Hong Kong. The delicate glass light tubes fashioned by Master Wu Chi-kai and the frames made by “Lee Wah Art & Frames” are both evidence of Hong Kong’s fine craftsmanship. With perseverance, these masters continue to innovate and refine their crafts, creating time capsules for the city’s colourful memories.

Neon Signs

Preserving Hong Kong's Neon Legacy

In a factory located at Lei Muk Road in Kwai Chung, Master Wu Chi-kai’s hands move nimbly between glass tubes and flames. He skillfully holds a long, thin glass tube in his hands, letting the flame heat it up and soften it. He then bends it into various shapes and keeps blowing air into it. As the piece of tube is heated in the flame, time seems to run backwards to the colourful 1980s and 1990s — the golden age of neon lights in Hong Kong.

Back in those days, most owners of retail stores, restaurants, cinemas and nightclubs adorned their premises’ facades with neon signs. When night fell and the city lit up, neon signs of all shapes and sizes hanging throughout the different commercial districts illuminated the whole city. The flickering red, green, and yellow lights reflected on the pavements, enveloping Hong Kong in a vivid and flamboyant cloak.

Master Wu started his career as a neon tube bending craftsman in the mid-1980s, during the peak era of the craft. “The neon industry in Hong Kong prospered because no other lighting technology could simulate its effect,” recalls Master Wu. “Back then, people didn’t have cell phones. Unlike nowadays, when everyone uses Google Maps, shop signs were the only way for customers to find stores, hence every shop owner invested in a neon sign.”

Master Wu remarks that, due to Hong Kong’s limited space and dense population, its entertainment and commercial districts were concentrated in its downtown areas. Signs for restaurants, pawn shops, goldsmiths, bookstores, cinemas and all kinds of businesses festooned the city. “During that period, shop owners would invest in a large sign if there were other signs blocking their sight line, in order to promote their business effectively. That was the period when the neon sign industry really thrived,” Master Wu continues.

Master Wu’s works can be found across all districts in Hong Kong. His most famous works have included those for Fook Lam Moon Restaurant in Wan Chai and Mido Café in Yau Ma Tei. He also created the famous “Marlboro sign” on the rooftop of the International Funeral Parlour in Hung Hom, as well as the neon wall of the Bank of China Tower in Central, to name but a few. Master Wu’s works are famous landmarks that symbolise the collective memories of Hong Kongers.

At the age of 57, Master Wu is one of remaining seven or eight neon sign masters who are still practicing the craft in Hong Kong. After many years of hard work, his neon signs have been illuminating Hong Kong past and present.

A Lifelong Career

Master Wu joined his profession at the age of 17. He recalls, “My father was a neon sign installer at a firm named Terry Neon Company Limited and he brought me to work during my summer holiday.” As installers sometimes have to risk working at height during the installation process, Master Wu took his father’s advice and started his learning at ground level — bending glass tube.

Back then, there were five or six masters working in the factory with ten apprentices, of whom only three specialised in neon light production while the others were mostly trained in installation. Master Wu was soon persuaded to stay; he recalls: “I was identified as a quick potential learner in neon sign making, so my boss persuaded me to stay and join their team. He told me that learning a skill is much more practical than going to school for a living.” At that time, Master Wu was also not particularly interested in study, so he decided to leave school and start his apprenticeship.

“Master Wu says that the apprenticeship was not the most challenging part; it was learning to be extremely patient and steady his hands.”

The production of neon lights is an extremely complicated process that involves designing, bending and blowing glass tube, connecting lamp heads, electrodes installation, vacuumising, gas filling, sealing, and finally testing. Master Wu says that the apprenticeship was not the most challenging part; it was learning to be extremely patient and steady his hands. He continues: “Glass is quickly softened under high temperature, and can be easily deformed or even cracked if your hands are shaky.”

As a teenager, Master Wu was required to work for long hours in the factory: “Even though we were apprentices, the senior masters were reluctant to teach us, because they thought once we learned from them, we would become their competitors. The only way we learned their skills was to observe their work, and keep practicing on our own.”

Turning Point

Master Wu started with the basics of welding lamp electrodes and went on to master the various neon production techniques step by step. After a few years, his performance was recognised by his boss and he was then assigned to open branches in Taiwan and Japan, while learning about their operation models.

During his time in Japan and Taiwan, he realised that Hong Kong had a competitive edge in the industry: neon sign companies in Hong Kong could import high quality materials from overseas due to its low tariff policy. By contrast, constrained by the need to use local materials, the colour vibrancy and lighting quality of neon signs made in Japan and Taiwan was of a lower quality.

A few years later, Master Wu returned to Hong Kong and opened his own studio with friends. As a neon sign is made of glass, it is highly stable and not easily affected by changes in temperature and humidity, making it an ideal choice for outdoor signage. In the good times, even though the price of neon signs was several times higher than that of plastic light boxes, businesses were willing to spend hundreds of thousands of Hong Kong dollars to create huge and eye-catching signs to attract customers.

“The 1990s were the heyday of neon signs,” Master Wu recalls. There were only around 10 neon sign production companies in Hong Kong and, during the peak period, Master Wu’s orders were coming so thick and fast that he could barely take a break between shifts. At his busiest time, he earned around fifty to sixty thousand Hong Kong dollars per month. “We had no time to go home to sleep as we wanted to catch up with work through the night. When we were tired, we slept on folding beds for a few hours, then woke up and started working again!” he laughs.

Throughout his career, Master Wu had a few unforgettable moments; he recalls one: “In the past, there were no LED lights, and most stage lights were neon. Once, during a concert at the Hong Kong Coliseum, one of the tubes broke, so I rushed off to repair it, then brought it back. On my way back to the concert, I unexpectedly ran into the singer Anita Mui, who sang for me!”

Creating neon signs requires

collaboration with various parties.

Wu Chi-kai

Neon Sign Master

Design and Production

Master Wu recalls how the earliest neon lights could only emit red light, as only neon gas was used in the early production period. As technology advanced, argon gas and mercury combined were found to produce blue light. With the addition of fluorescent powder into the tube, neon lights then produced a variety of colours.

Neon sign making is a craft that requires both skill and patience. Firstly, tubes with diameters ranging from 12 to 20 mm are heated in a flame; then, they are twisted into various shapes by hand, while air is blown into the tubes to ensure that the bent parts maintain their original shape under the high temperatures. This process demands a high degree of craftsmanship, especially when making neon signs with traditional Chinese characters, which have many strokes. “I used to hate making signs for restaurants, clinics, and seafood restaurants because of the strokes; it was difficult to create those signs,” says Master Wu with a smile.

Creating neon signs requires collaboration with various parties. “In the past, a signboard could be as tall as a floor. After a calligrapher finished writing the characters on the paper, we enlarged each word, and cut and assembled it into parts for further production. Strictly based on a 1:1 ratio, we then bent the light tubes to the shape, connected the heads of the lamps, and vacuumised and filled the tubes with inert gases. Finally, we handed it all over to the installers for on-site assembly like a jigsaw puzzle,” Master Wu explains.

He says the process of making neon tubes could be quite boring, as workers needed to keep repeating the same steps over and over again throughout the day. Yet neon sign installers faced a lot more challenges: “One time, we even had to install neon lights for a client on a boat moored at Kulangsu Island. We left home early in the morning and took a ferry there. After the job was finished, we returned home by dinghy.”

The experience from Kulangsu Island reminds him that design, and the practicality of installation, are two closely-related concepts: “Some signs would be too difficult to assemble if you designed them without considering the installation process,” he explains. With this insight, Master Wu later improved his production technique, for example dividing pipes into more segments during the design stage, to facilitate on-site assembly.

Sketching the design from the customer brief

Sketching the design from the customer brief

Connecting the lamp tube (electrodes) to the base

Air is removed from the glass tube using a vacuum machine, and is replaced with neon or argon gas. The tube ends are then sealed, and the process is complete

With this insight, Master Wu later improved his production technique, for example dividing pipes into more segments during the design stage, to facilitate on-site assembly.

Passing on the craftsmanship

In the mid to late 1990s, however, the local neon sign business was hit hard by the emergence of a new production market — Shenzhen, China; massive flows of production orders were sent there instead of Hong Kong due to the much cheaper prices. “During that time, the small neon signs on the streets were rarely made locally”, he recalls sadly. So he shifted his focus to large-scale projects, such as the triangular neon sign on the exterior wall of the Bank of China Tower in Central; and the semi-circular spherical neon installation on the rooftop of Langham Place in Mong Kok.

After the millennium, neon was eventually replaced by cheaper and more flexible LED lights. Master Wu continues: “Neon is just a tube of light that is heated and made into different shapes, and its colour remains the same. But LEDs are different: they can change colour within a limited space and are cheaper to install and maintain. So most businesses are switching to LEDs without hesitation,” he says. In 2010, the Buildings Department of the HKSAR tightened its regulations on signage, leading to more giant neon signs being dismantled in Hong Kong.

As more and more neon signs craftsmen retire, the local craftsmanship is gradually dying out; this also led Master Wu to consider leaving the industry. However, whenever he was thinking of quitting, new opportunities would always come his way.

In recent years, with the increased awareness of the need for cultural preservation, neon lights have regained favour. To commemorate the dismantled peacock sign at Millie’s Centre located in Jordan, Master Wu made a replica for an exhibition in 2014. He also participated in the restoration of the signboard at the M+ Museum. Besides his experience in neon lighting, he also served as the technical advisor for the film “A Light Never Goes Out”, produced in 2022. In addition, he has also collaborated with various galleries, exhibitions, wedding companies and interior designers.

Master Wu has been gradually shifting his focus from commercial applications to artistic creations: “Many artists want to design something special featuring neon light, but they are not familiar with the techniques. So I am here to give advice, and ensure the product can be effectively made.” He reveals that he started doing research about the production of three-dimensional neon lights around twenty years ago, and he plans to hold a three-dimensional neon light exhibition to showcase the unique charm of this craft.

When young neon artists come to Master Wu for mentorship, he is happy to pass on his skills and knowledge. Despite the growing popularity of LED lights, Master Wu still firmly believes that the artistic value of neon signs will never fade: “As long as there is demand, the culture of neon will be passed on and preserved,” he says.

“As long as there is demand, the culture of neon will be passed on and preserved.”

Lee Wah Art & Frames

Generations of Framers

Walking down Chancery Lane in Central, you may spot a low-profile, single-storey shop tucked between the skyscrapers — this is “Lee Wah Art & Frames” (“Lee Wah”). Pushing open the entrance door, you immediately enter a quiet workplace, that starkly contrasts with the bustle of the street. With over 40 years of expertise, “Lee Wah” is a traditional framing shop renowned for its fine framing techniques. Hundreds of frames hang on the walls — from highly-ornamental gilded examples, to the plainest of wooden designs. Each is waiting to partner with precious artworks and collections from customers all around the world.

Ernest Chan, who currently runs “Lee Wah”, is the second-generation owner of this shop. He is responsible for handling enquiries and orders, framing and mount cutting. His parents, Peter Chan (Mr. Chan) and Jeannie Ho (Mrs. Chan), also work in the shop as assistants.

“Hundreds of frames hang on the walls — from highly-ornamental gilded examples, to the plainest of wooden designs. Each is waiting to partner with precious artworks and collections from customers all around the world.”

From Importer to Framer

Ernest’s father, Mr. Chan, originally worked as a framing supplies importer, specialising in raw materials from Europe and the USA. He recalls: “In the 1980s and 1990s, the frames were mostly hand-made; it was not easy to find the raw materials for making them. Originally, we only worked as an agent, importing our supplies from Europe and the USA. The original owner of ‘Lee Wah’, who is now our long-time customer, returned to Malaysia and invited us to take over the business in the 1990s. At that time, we also wanted to expand the business, so we agreed to take it over.”

The shop’s name, “Lee Wah”, originated from its founder, Mr. Lee. Mr. Chan decided to keep the shop’s name because it was already well-known and had a good reputation in the industry, and the shop’s original staff members had agreed to stay. Mr. Chan said that in the 1980s, 60–70% of the shop’s customers were from overseas; Hong Kong, being a place where East meets West, has long attracted foreigners to make it their home.

In Europe and the USA, preserving artwork is not just for protection, it’s part of their culture. “Many of our foreign customers, even if they just stay in Hong Kong for a few years, spend a lot of effort preserving their artwork and photos. To them, both pictures and their frames can significantly change the ambience of a space,” Mr. Chan explains. “Lee Wah” is renowned for its craftsmanship, especially among foreigners living in Hong Kong; this is one of the reasons the shop is alive today.

Integrating professionalism and tradition

Ernest grew up watching his father managing the framing business, but he chose to take a completely different path. He majored in engineering at university, and worked at a multinational company after graduation; he only helped in the shop at weekends. But when he turned thirty, he decided to take over the shop. To gain more professional knowledge, he even obtained a Certified Picture Framer (CPF) licence from the Professional Picture Framers Association (PPFA).

Through systematic training, Ernest learned to handle artworks carefully to prevent them from being damaged; he has also learned the importance of reversible framing. “Most collections must be protected by UV-resistant glass and acid-free backing boards, as Hong Kong’s humid climate and strong ultraviolet rays may damage the artwork,” he explains.

He goes on to give other examples of the special precautions taken in framing: “For instance, acrylic does not compatible with charcoal drawings, as its static electricity attracts charcoal from the paper.” He continues, “We never touch photos with our hands as the oil on our skin leaves marks — so it’s necessary to wear gloves. And, if we want to roll up an old oil painting for storage, we never roll it inwards, only outwards. Rolling inwards cracks the dried oil on the painting.”

In addition to what he learned at school, Ernest observed the masters’ framing skills in the shop. “For example, if we want to mount a large frame on the wall, we may consider adding wooden battens to stabilise its structure. A larger art piece such as 2 m x 2 m requires more support at the back; the size and weight of battens is a matter for the master’s experience.”

Most collections must be protected by UV-resistant glass and acid-free backing boards, as Hong Kong’s humid climate and strong ultraviolet rays may damage the artwork.

- Ernest Chan

Owner of Lee Wah Art & Frames

Embodiment of memories and sentiments

“Lee Wah” welcomes all kinds of customers from curators and collectors to young adults of the local neighbourhood. Some come to the shop with masterpieces worth several million Hong Kong dollars, while others bring their kids’ first drawing for framing. This small shop has become an embodiment of the memories and sentiments of countless customers.

Over the years, “Lee Wah” has framed many works by masters such as Zhang Daqian, Chi Pai Shih and Wu Guanzhong. “We offer one-stop services at our shop, and we never outsource any work to the Mainland,” says Mr. Chan proudly. “This is the reason people choose us.” He says that many of their customers are very loyal: “Some of them came here for framing their wedding photo one or two decades ago, and then returned for a frame replacement for the same photo.”

This small shop has become an embodiment of the memories and sentiments of countless customers.

Ernest’s mother, Mrs. Chan, adds: “Once a collector brought a painting by Zhang Daqian for framing, worth a few million Hong Kong dollars. To ensure the painting was safe, the owner stayed in the shop and monitored the whole framing process. We were all very nervous: after all, we were responsible for the painting!” Other customers brought in old and moldy paintings for restoration. Mrs. Chan says seeing their customers smiling in satisfaction at the restored paintings is their happiest moment.

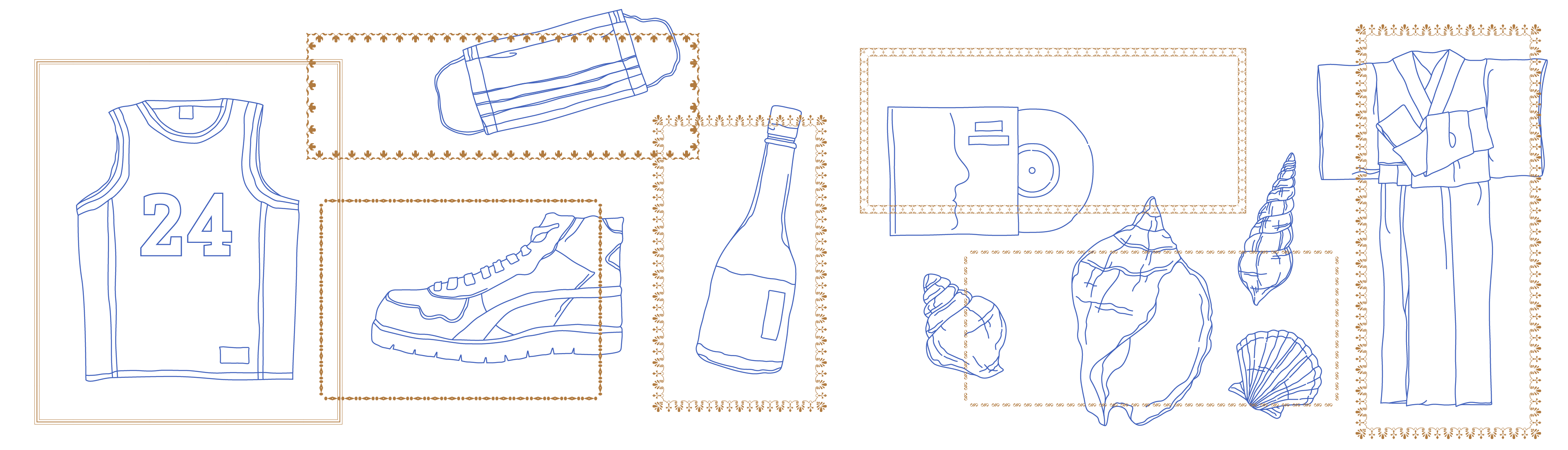

Since Ernest took over the business, he has encountered many special requests from customers. He believes that everything can be framed and so he always tries his very best to accommodate customers’ demands: “Someone requested us to frame three shells, but three-dimensional objects are among the most challenging things to handle. Unlike a 2D painting, you have to consider the object’s thickness, and the best way to frame it. Another example was a vinyl record; we could not use any glue or tape, because that would have damaged its surface. I tried various ways such as transparent plastic boxes, magnets, fishing line and homemade structures to fix the record’s position inside the frame.”

Apart from paintings and photographs, “Lee Wah” has also framed jerseys, autographed sneakers, wine collections, kimonos, and even a COVID-19 Vaccine Pass and face mask for a foreign visitor before he left Hong Kong. Framing is rather like the art of mixing and matching clothes: there are dozens of different ways to frame the same object, but different combinations convey different moods and feelings. Ernest designs a frame based on the size, colour and medium of the work. Whether the artwork or photograph is plain or colourful, the most important thing is that the frame design highlights the subject.

Mrs. Chan believes customers nowadays have much higher expectations than those in the past. She explains: “In the past, very few customers requested museum glass to frame their collections, but many now specify this high-end material.” Even if the work itself is not worth much — for instance, a child’s painting — parents will often spend a thousand Hong Kong dollars to frame it, simply to preserve their precious memories. “After expert framing, even an ordinary painting is transformed into a ‘masterpiece’,” she adds. “Our customers are all delighted to see this!”

“Framing is rather like the art of mixing and matching clothes: there are dozens of different ways to frame the same object, but different combinations convey different moods and feelings.”

Perseverance in a time of change

To keep a shop running successfully, passion alone is not enough. Ernest says, due to the rapid changes in Hong Kong’s market, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a decline in the number of visitors coming to Hong Kong in recent years, and this has created tremendous challenges for artisan shops like “Lee Wah”.

Mrs. Chan also shares the changes in the industry over the years. In the past, framing Chinese paintings and calligraphy required meticulous skills, as the masters needed to know how to make rounded-corner frames. They also needed to paint the frames themselves. All these steps relied heavily on the masters’ aesthetic sense and craftsmanship. As many masters have retired in recent years, the traditional craft of framing Chinese paintings has been fading away.

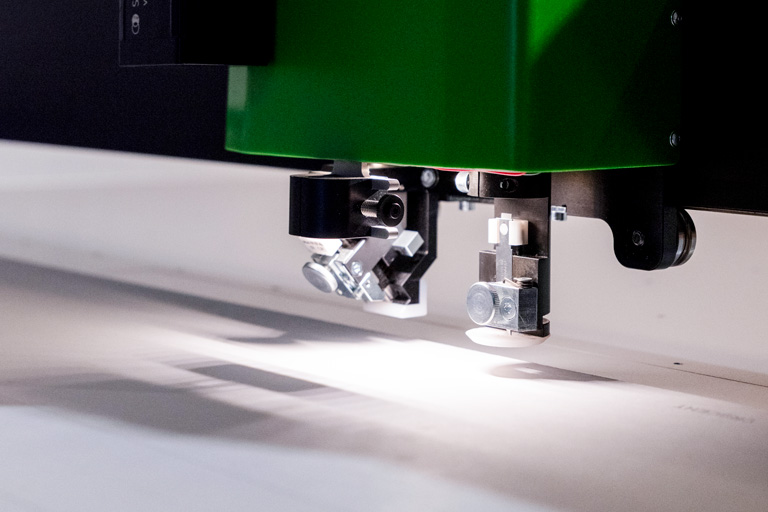

Since the production of frames requires meticulous craftsmanship, Ernest has tried various ways to control costs and maintain quality, by introducing machinery into the framing process; machines are now used for cutting cardboard, frame materials and glass. This allows the masters to focus on framing, which requires more experience as they may need to make adjustments according to the work’s texture. Lack of skilled manpower has become the biggest challenge.

“There used to be several skilled masters working here but, after they retired, it has been extremely difficult to find replacements,” says Ernest. The art of framing requires an aesthetic sense of proportion, dexterity, and sensitivity to different materials. This art can’t be acquired just by completing a course. “That is the reason why this kind of craftsmanship can never be totally replaced by machines,” he adds.

I hope to continue serving local galleries, artists, and collectors in Hong Kong, upholding our high standards and preserving traditional craftsmanship.

In recent years, Ernest has taken the initiative to train new blood, recruiting young people who are passionate in arts and design to work as part-time staff members. As Hong Kong’s art market matures, art fairs such as Art Basel Hong Kong and Art Central continue to attract global attention, driving demand for quality framing services from local galleries and collectors.

“We have worked with some of the galleries participating in Art Basel Hong Kong, though many of their paintings shipped from overseas already include pre-made frames. On the other hand, some local galleries and buyers also come to us for re-framing services.” Ernest has also observed that Hong Kong collectors have tended to buy bigger paintings in recent years. “In the past, most of the framed objects were small collections, such as souvenirs bought during travels. That trend has changed and nowadays more customers prefer larger works,” he explains.

Talking about his future plans, Ernest said he does not intend to leave Hong Kong or expand his business at the moment; instead, he is focused on maintaining the personalised service and artisanal quality of his framing business. “I hope to continue serving local galleries, artists, and collectors in Hong Kong, upholding our high standards and preserving traditional craftsmanship,” he concludes.

Time capsules of memories

Neon signs and frames both convey memories, and witness the passing of time. While Master Wu Chi-kai has created countless neon signs that illuminate Hong Kong, the Chans at Lee Wah Art & Frames have preserved many art collections with their skillful hands. Making neon signs and preserving artworks involve complicated processes, and require the craftsmen’s adherence to detail. With their passion and skills, Master Wu and the Chans have helped preserve the precious memories of Hong Kong.