In 2018, Super Typhoon Mangkhut swept through Hong Kong, smashing down common trees such as Chinese Banyan, Tree Cotton and Flame Trees across the city. These humble trees used to provide shelter for people during the rain, but they instantly became road blocks after the storm. Sadly, most of these trees became landfill waste. Following Typhoon Mangkhut, it was the first time that the city started discussing how fallen trees might be dealt with differently.

Says young carpenter Yung Wing-yan (Yan): “I started learning woodcraft before Typhoon Mangkhut. I always went around to see if there was any fallen tree or unwanted wood that I could collect from tree removal projects. It was then that I realised they were all going to landfill: it’s such a pity!

“All trees, old furniture or even abandoned wood are valuable resources, that can be regenerated into something useful,” adds Yan, who founded “Cou Tou Studio” (“Cou Tou”). We visited this social enterprise to see how they give a second life to old wood, while bridging the two generations of carpenters.

“All trees, old furniture or even abandoned wood are valuable resources, that can be regenerated into something useful.”

Wisdom of Hong Kong carpenters

Yan is now an advocate for conservation and a carpenter who upcycles abandoned wood. Interestingly, she started her career in advertising, which promotes consumption. “I just wanted to get a well-paid job and make a lot of money after graduation, so I went to France to study advertising,” says Yan. But life’s unexpected twists and turns led her in a different direction. Her greatest reward during her study in France was not learning about advertising, but learning how the French value life more than material things, and how people try to make things with their own hands. “I worked in an advertising company for a while after graduation, but I left because I thought it was not for me. At that time, I had no clue what I wanted to do, I just wanted to learn a creative craft,” Yan said.

Yan was introduced to woodcraft through her wood crafting friends. She went to Taiwan to study the craft, then made friends with some local carpenters in Hong Kong. After getting to know these old masters, Yan realised each of these ordinary-looking old carpenters had their own philosophy behind their craft, which continued to inspire Yan’s craft and her way of thinking. “Take Lung Tsai as an example,” she continues. “He’s an old master whom I truly respect. He comes from a grass-root background and he’s used to doing woodwork for home renovation projects. He doesn’t talk about theories. If you ask him to make a chair, he can do it even if there are not enough tools or space. He uses whatever is available and makes the best of it,” says Yan. When she first started learning woodcraft, she insisted on doing a particular task with a particular tool, for example drawing lines with a marking gauge. “I felt inspired and enlightened after meeting old masters like Lung Tsai. I realised training my problem-solving skills and learning to be flexible is the essence of creation,” adds Yan.

Upcycled wood carries heritage

As Yan says, abandoned wood is a precious resource. In Hong Kong, 380 tonnes of wood waste are thrown away every day, including waste from construction, wooden pallets and furniture, fallen trees and rattan. Unfortunately, only 0.4% of these materials are currently recycled. This motivated Yan to find better ways to make use of unwanted wood, and she eventually established “Cou Tou” in 2017. At this social enterprise, she designs and creates furniture by upcycling abandoned wood.

Today, “Cou Tou” collects most wood from waste stations and also receives donations from schools and individuals. Each piece of wood has its own story, linking individuals and community. “A tall Acacia confusa tree fell down in a school some years ago. At that time, the school asked a saw mill to cut the logs into lumber, which was then kept in the school’s storage room. Later, the school invited us to investigate how they could reuse the wood, so we decided to make a table for the library, while the offcuts were used by carpentry class students,” says Yan. The tree that once provided shelter for students has now been transformed, yet still keeps the students and the community company.”

Sometimes, stories of wood donations from individuals can be touching. “I’ve a student who learns woodcraft from me. He and his family are all Christians. When one of his family members passed away, his church was undergoing renovation, and a teak door was left over. So he asked us to make an urn box with the wood, as a remembrance,” explains Yan. Not only did the wood gain a new life: it was turned into something tangible that connects people across time and space. Yan stresses once again that such unwanted wood is not simply waste, but a treasure that can tell a moving story.

“I felt inspired and enlightened after meeting old masters like Lung Tsai. I realised training my problem-solving skills and learning to be flexible is the essence of creation.”

New journey of an old conference table

The collaboration with Hong Kong Air Cargo Terminals Limited (Hactl) is one of Yan’s most recent projects. By recycling the terminal’s old furniture and abandoned wood, “Cou Tou” is helping Hactl create a range of upcycled furniture and art pieces. Among these artefacts, a particularly meaningful one is a transformation of the former conference table from Hactl’s boardroom on the sixth floor. This table witnessed many crucial decision-making moments, and had been in use since Hactl’s days at the old Kai Tak Airport. Although the condition of the wood is still good, the table itself had worn out after years of heavy use. With creativity and craftsmanship, Yan and her team have given the table a new lease of life: “By re-cutting the wood, polishing it, then combining the various pieces together, we’ve created an upcycled high table and stools that can be moved around for various purposes,” says Yan. Instead of joining the wooden pieces with screws and nails, the team employed mortise and tenon joints, a traditional jointing method that demands precise measurement, fine cutting and great skill. “Woodcraft is not only about making products, we also need a knowledge of mechanics, structure and materials. Using old wood to create upcycled products doesn’t mean they have to look rough; the products can be very fine too,” declares Yan.

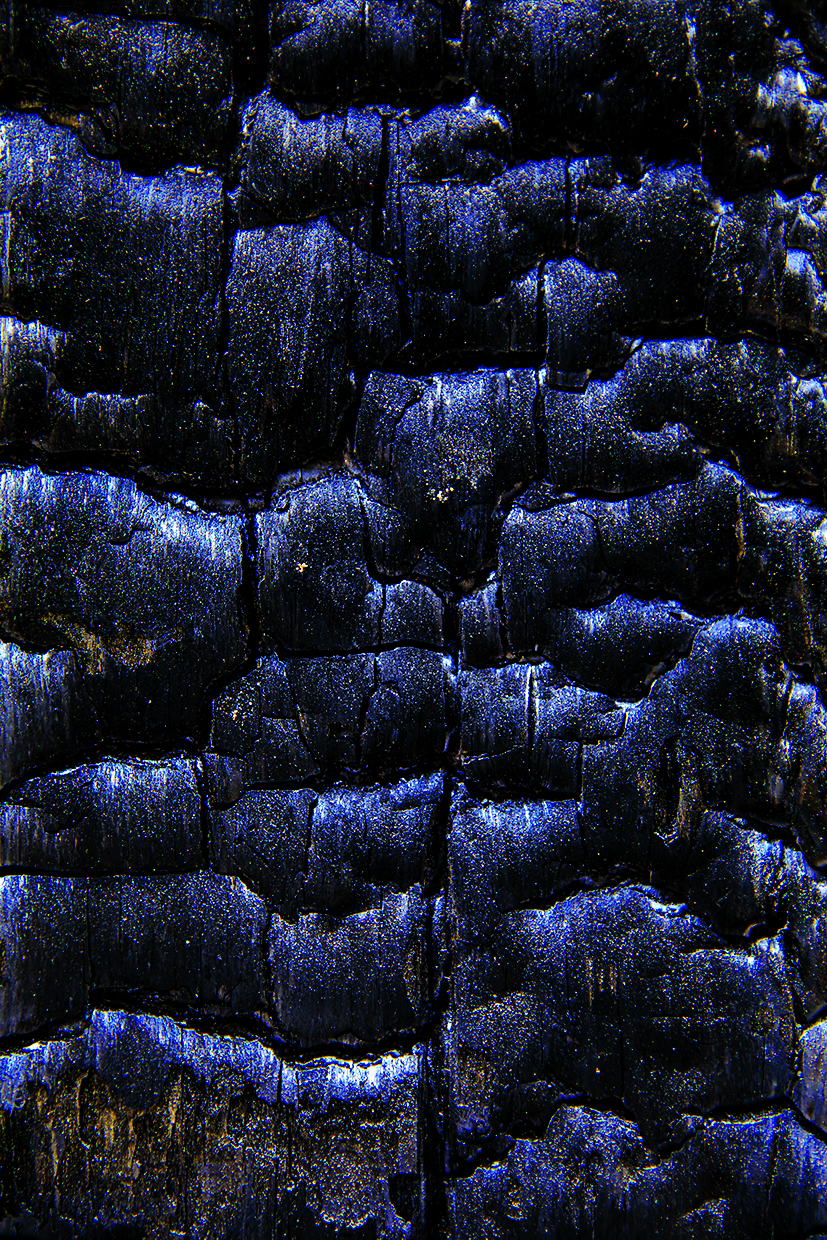

Besides upcycling old furniture, “Cou Tou” also makes use of wooden pallets – an object commonly used to carry cargo within Hactl’s SuperTerminal 1. The carpenters first remove the nails from the pallets, then they plane the wood surfaces, and glue the different pieces together. After some reshaping and polishing, the pallets are turned into various upcycled furniture and installations. “Wooden pallets are strong and resilient: that’s why they can carry heavy cargo. By mix-and-matching different tree rings, they can form many interesting patterns, so wooden pallets are ideal materials for making decorative furniture,” Yan explains about how her team creates upcycled furniture for Hactl.

“Wooden pallets are strong and resilient: that’s why they can carry heavy cargo. By mix-and-matching different tree rings, they can form many interesting patterns, so wooden pallets are ideal materials for making decorative furniture.”

Uniquely creative upcycled furniture and art pieces made from discarded wooden pallets collected in Hactl's SuperTerminal 1

Connecting old and young carpenters

We ask Yan to name the piece that she is most proud of over her years of wood crafting. She ponders – and, surprisingly, what makes her proud is not any one particular product. “What I feel most proud of is that ‘Cou Tou’ has become a platform passing on the art of wood crafting. When young people who are interested in wood crafting come here, they can meet old carpenters who have so much knowledge and so many stories to share,” Yan continues. Besides designing upcycled wood crafts, “Cou Tou” also runs courses and provides employment opportunities for young people wanting to develop their careers in wood crafting. “Everything is about efficiency in Hong Kong, there is no room for exploring what you want to become. I’ve been very lucky to have found my way through wood crafting, so I hope young people can also discover the many possibilities in life, through learning the craft,” says Yan.

She adds, “When I was an apprentice, I met many wonderful old masters like Lung Tsai who were very generous in teaching the younger generation.” As many of the old carpenters recall, Hong Kong’s wood crafting industry used to be very prosperous in the 80s, but as factories gradually moved to the Mainland, the trade slowly died out. “The quality of woodcraft in Hong Kong is no less than in other countries, but we have not handed down the craft or developed it. So I hope ‘Cou Tou’ can act as a bridge connecting the older and younger generations through woodcraft, while advocating for better use of the city’s resources, and refining our work and making it more professional,” Yan continues hopefully.

Looking at the products made by “Cou Tou”, one can see the interaction between old and young carpenters, and be reassured that the city has found a better way to make use of its fallen trees and abandoned wood – rather than just dumping them in landfill.