Mahjong tiles and “Gangcai” – Hong Kong painted porcelain – are the products of different crafts with different markets. The general public loves to spend its leisure time playing Mahjong with family and friends, while Chinese and foreign dignitaries and celebrities savour the distinctive and delicate style of “Gangcai”. These two artefacts reflect the diverse ways of life and interests of people from different social classes in Hong Kong.

More importantly, as part of the unique Hong Kong culture in which East meets West, hand-carved Mahjong tiles and hand-painted “Gangcai” have been absorbed into the prestigious world of Hong Kong craftsmanship, which never ceases to delight the world. The traditional shops we visit in this edition of “Flavours of Hong Kong” – “Yuet Tung China Works” (“Yuet Tung”) and “Kam Fat Mahjong” (“Kam Fat”) are two examples of the few remaining family-owned shops in their industries. Their two owners have witnessed the most prosperous days of “Gangcai” and hand-carved Mahjong tiles, and are keeping this traditional craftsmanship alive today.

Their shops are de facto living museums, and each work piece provides a treasured glimpse into the city of a bygone age…

Gangcai

Yuet Tung: eastern porcelain prized in the West

An intriguing aspect of our first visit to “Yuet Tung” is seeing the letters from customers – each of which tells its own story – collected by the shop’s third generation owner, Tso Chi-hung, Joseph (Joseph). In 1986, after the visit of the Queen and Prince Philip to Hong Kong, a letter was sent to Joseph by Peter Hore, Commander of the Royal Navy, thanking “Yuet Tung” for the commemorative porcelain plates made for the luncheon in honour of Prince Philip. The letter specifically mentioned Prince Philip’s personal appreciation of the porcelain. Another letter from 1984 mentions the visit of Vice Admiral James Hogg of the U.S. Seventh Fleet, during his trip to Hong Kong. After purchasing some porcelain, he sent an official letter of praise to “Yuet Tung”, with the enthusiastic handwritten footnote – “Your factory is the best!”.

Tall and slender, Joseph looks like a literary figure from olden days, squinting at the letters and unveiling the story of “the best” painted porcelain of “Yuet Tung”, which has stood in Hong Kong for almost a century.

Guangcai seen through the eyes of foreigners

World-renowned “Yuet Tung” evolved from a more traditional porcelain painting craft from Guangzhou – “Guangcai”. In 1928, Tso Lui-chung, Joseph’s grandfather, founded the “Kam Wah Loong” factory in Kak Hang Tsuen Road, Kowloon City, Hong Kong. The factory kept running until the outbreak of the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression in 1941, and eventually reopened in Cheung Sha Wan in 1947. “At that time, as the location of the new factory was previously the ‘Yuet Tung Hotel’, grandpa named the new factory ‘Yuet Tung China Works’, and the name is still in use today,” explains Joseph.

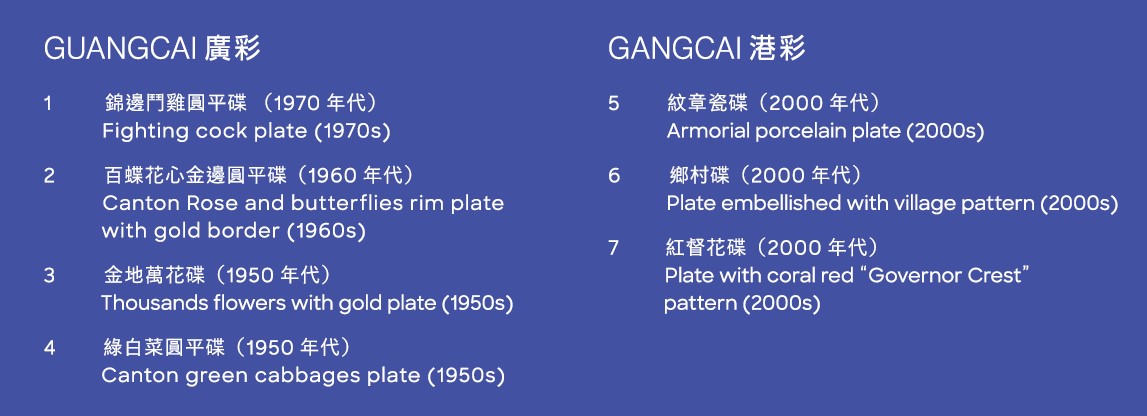

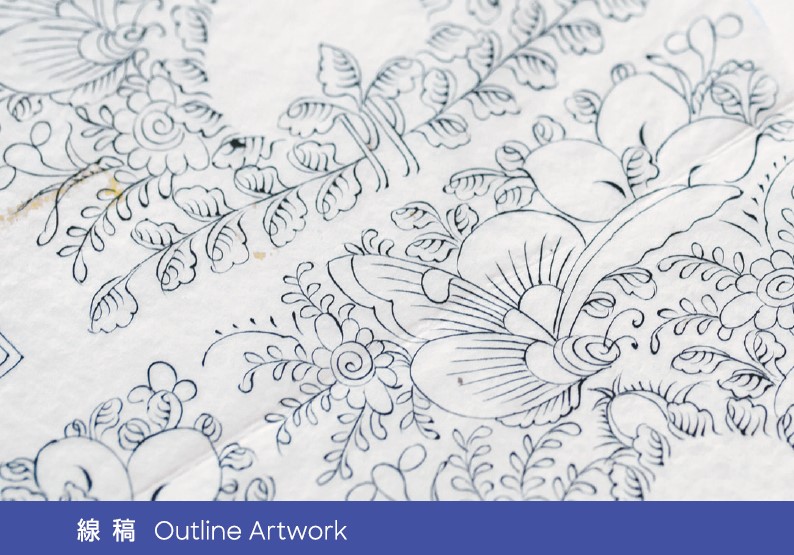

The history of “Yuet Tung” reflects that of modern China, Hong Kong, and even the Cold War era. Since the mid-18th century, Guangzhou had become an important foreign trade port in China, and businessmen from all over the world came there to trade. “The fired white porcelain bodies were shipped from Jingdezhen of Jiangxi to Guangzhou for hand painting by local masters, before being exported to the world. That is the origin of ‘Guangcai’,” says Joseph. “They can be large-scale artistic works for display, or porcelain tableware for everyday use.” He talks about the history of “Guangcai” like a scholar: “‘Guangcai’ is characterised by complex composition, traditional charm, and sophisticated brushstrokes. The master first creates the outlines with black paint, and then carefully fills in the colours.”

"‘Guangcai’ is characterised by complex composition, traditional charm, and sophisticated brushstrokes. The master first creates the outlines with black paint, and then carefully fills in the colours."

Joseph reveals that “Canton Rose” is a classic pattern of “Guangcai”. Take a closer look at the porcelain plate painted with the “Canton Rose”, still for sale in “Yuet Tung”: the petals, buds and green leaves are gorgeous and can take hours to study. There is little empty space on the porcelain plate: much of it has been coloured in gold. “The master paints golden lines on it, as if weaving a gold-threaded dress. We call this style ‘Weaving Gold Feathers’.” This traditional style of “Guangcai” work, which is extremely painstaking, has been out of production since the 1990s. The only hand-painted pieces remaining in the shop are the work of old masters from the 1940s to 1960s.

Today, Joseph is a well-known authority in Hong Kong’s painted porcelain industry, and has even published books on the subject. But when he was young, he didn't know how famed his family business was: “When I was a child, I only knew that my family painted patterns and figures on bowls and plates. I only helped by packing the porcelain for customers. After graduation, I began to receive customers and found that many foreign guests exclaimed at the ‘Canton Rose in Medallion’. Then I realised that the ‘figures’ and ‘roses’ painted by masters were called ‘Guangcai’. So I started studying scholarly monographs and the catalogues of auction houses. When I had opportunities to visit museums in foreign countries, I paid extra attention to ‘Guangcai’ porcelain and became more and more fascinated by it.”

Joseph Tso - the third generation owner of "Yuet Tung"

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Gangcai reflects modern history

With the outbreak of the Korean War in the 1950s, the US embargoed China’s export of fine porcelain from Guangzhou. The political turmoil also caused quite a few Guangzhou masters to migrate south to Hong Kong. This blessed land had unexpectedly become the export hub for painted porcelain in those chaotic times. Foreign department stores came to Hong Kong porcelain factories for bulk production. At the industry’s peak in the 1970s, there were more than a dozen porcelain factories in Hong Kong. “In our heyday, ‘Yuet Tung’ had 50 workers, and we even had to set up workshops in Cheung Chau and Peng Chau to keep pace with demand.” Today, Peng Chau’s popular souvenir shop – “Chiu Kee Porcelain”, is owned by a former worker at “Yuet Tung”.

It is interesting to note that the traditional craft of “Guangcai” has slowly evolved into a new style of “Gangcai” – a painted porcelain that inherits the techniques of “Guangcai” but is simpler and more modern. After the 1960s, European customers not only came to “Yuet Tung” to order the more traditional “Guangcai” porcelain, but also to order coloured porcelain decorated with their own family crests, which were no longer available in their home country. Sometimes, they requested Chinese patterns to represent their family’s coat of arms or castles, and the masters applied traditional craftsmanship to create a new world of “Gangcai” combining both Chinese and Western elements.

“Before placing an order, foreign customers would collect their favourite patterns and compile a small selection of drawings with descriptions for masters to refer to,” Joseph explains. Speaking of “Gangcai”, we must mention the “Governor Crest”, of course. In 1975, Lady MacLehose, wife of Sir Murray MacLehose, the former Governor of Hong Kong, brought a treasured item of family blue and white porcelain, hoping that “Yuet Tung” would recreate a set of painted tableware for her. This became the unique pattern of “Yuet Tung”, and still very popular today. Due to the exquisite quality of “Yuet Tung’s” products, local hotels such as the Four Seasons, Mandarin Oriental, Shangri-La and the Peninsula frequently purchase porcelain tableware from “Yuet Tung”, while political bodies such as the Legislative Council, major chambers of commerce and large corporations also place orders with “Yuet Tung” for commemorative items.

He still has to rely on his master craftsmen to draw lines and patterns on the white porcelain body.

To industrialise the fine art

Despite its status in the “Guangcai” and “Gangcai” industries, painted porcelain is a matter of slow and careful work, and “Yuet Tung” has always faced the challenge of how to industrialise its creations. Joseph says that, although he has lived his whole life among painted porcelain, his skills are limited to colouring it – and he still has to rely on his master craftsmen to draw lines and patterns on the white porcelain body. After the embargo on Guangzhou’s porcelain in the 1950s, “Yuet Tung” received so many orders that they had to work out ways of increasing output.

“At that time, the masters were very specialised in painting particular patterns – some focused on flowers, while some were best at roosters. Some had an artistic temperament, and would refuse to work if they were not in the mood,” Joseph says with a smile. As a result, Hong Kong’s porcelain factories were trying to introduce new methods of production: for example, craftsmen were asked to make rubber stamps of designs drawn in advance by the masters. The workers then used the rubber stamps to apply the outlines directly onto the porcelain products. Later, “Yuet Tung” also began to adopt “Decal Transfer” – applying decals directly to the white porcelain, so as to improve the production efficiency. To this day, there are two masters still serving “Yuet Tung”: most products are now made using the “Decal Transfer” method, and are then coloured and fine-tuned by the masters.

“However, young people have a wide range of interests and they return to their own lives after learning for a short period of time, rarely taking time to study the traditional craft of porcelain painting.”

Joseph takes the heritage of “Gangcai” very seriously. “I’ve spent my whole life in ‘Yuet Tung’ and it's part of my life.” Indeed, Joseph and his wife met because of “Yuet Tung” and “Gangcai”. “We got to know each other as my wife was helping foreign companies to buy porcelain at ‘Yuet Tung’.” Today, art galleries, cultural organisations and even shopping malls often contact “Yuet Tung” to organise workshops introducing “Gangcai” to the younger generations, and Mrs. Tso regularly gives talks to the public. “However, young people have a wide range of interests and they return to their own lives after learning for a short period of time, rarely taking time to study the traditional craft of porcelain painting.” But Joseph is not disappointed; at least the seeds of “Gangcai” are being sown in the next generation.

On the day of the visit, which was Chinese New Year’s Eve, we found many “Chuen Haap” (Chinese candy boxes) decorated with the “Governor Crest” pattern, stacked among the many items of porcelain, and asked if we could buy them on the spot. “All of them are orders from customers,” explained Joseph. “It is my daughter, Martina’s idea: she studied design and very much appreciates the craftsmanship of ‘Gangcai’. She promotes this product on the internet and the response is overwhelming.” In fact, his daughter has been actively helping with sales and promotion at “Yuet Tung” in recent years. At these words, the phone rang once again at “Yuet Tung”. “I’m sorry, but the “Chuen Haap” are sold out. The other tableware will be available after Chinese New Year,” Joseph tells the customer. It’s not easy to keep “Gangcai” going, but there are clearly many people out there who are still in tune with it: so maybe we don’t need to be too concerned about the future.

Mahjong

Kam Fat’s Mahjong “Wonder Woman”

When we visit “Kam Fat” around Chinese New Year, we greet Ho Sau-mai (Sister Mai), the owner of “Kam Fat” with “Happy New Year”. Sister Mai immediately replies: “Hey! I want to be happy every day, I don’t want to wait until the New Year!” This makes us all laugh. Sister Mai is in her early 60s: tanned, with short hair and a great sense of humour. That morning, in the 100-square-feet of her “staircase shop” (so called as it’s a tiny shop under the staircase of the tenement building), we listen to this amazing woman, as she tells us how she has been working hard in Hung Hom for decades to become a respected master carver of Mahjong tiles.

Like “Yuet Tung”, “Kam Fat” is all about skillful craftsmanship. One hundred and forty-four Cantonese style Mahjong tiles are the master’s canvas. Sister Mai first demonstrates how to carve a “Dot” tile for us. She takes out a bow-like carving drill from the back of the shop. After adjusting the blade of the drill with her left index finger, she quickly presses the machine’s bar with her right hand, while spinning the tile, so the pattern of the “Dot 9” tile becomes more and more pronounced. Before we can work out the operation of the drill, Sister Mai proclaims “Done!”

“Dot, Bamboo, Character, Honours and Flowers”: Sister Mai recites the patterns of the Mahjong tiles. She touches the blank Mahjong tiles and then carves different patterns by instinct: the result of half a century’s practice and hard work. When Sister Mai’s father immigrated to Hong Kong from Mainland China, relatives arranged for him to learn the carving skills from a Mahjong shop in the Central district. “Nowadays people say that hand-carved Mahjong is an art and culture; but in my father’s time, we didn’t think about that at all. We only did it to make a living. In the 1960s, before machine-carved Mahjong tiles became popular, hand-carved ones were the only option for players, so our shop was doing well.” In 1962, Sister Mai’s father opened his own shop –“Kam Fat”, on Bulkeley Street in Hung Hom. In its heyday, “Kam Fat” had three shops in Hung Hom, each with a Mahjong carving master, while her father focused on developing the business. “I used to watch the master carving, and tried to do it myself. The masters didn’t explain step by step,” Sister Mai adds. “Although I often skived off from my work, the master would never scold me as I was his boss’ daughter!” she adds with a laugh.

“Nowadays people say that hand-carved Mahjong is an art and culture; but in my father’s time, we didn’t think about that at all. We only did it to make a living.”

A half-century of carving mastery

Sister Mai had to endure a lot during her time as an apprentice. A single scratch can make a deep mark on the thick acrylic tile, so an accidental cut on the hands is nothing unusual. “It was no big deal, not a lot of blood was shed, so once I stopped bleeding, I could start working again.” She continues, “When you first begin carving a tile, the hardest part is looking at it and not knowing where to start. You don’t want to make a wrong cut and waste the tile.” I ask Sister Mai which tile is the most difficult to carve, “Difficult?” she instantly responds. “I’ve been carving Mahjong tiles for decades, and there’s not a single tile that’s difficult!” But after a moment’s thought, Sister Mai finally says, “The most difficult one is the bird-like ‘Bamboo 1’ tile, which is more complex, and the ‘Flowers’ tiles – ‘Plum’, ‘Orchid’, ‘Chrysanthemum’ and ‘Bamboo’ – each of which has to express both form and spirit.” Despite the fact that she always seems to be joking, Sister Mai knows that “Kam Fat” is the brainchild of her parents, and she takes it very seriously, “My father passed away in 1986, and my siblings were all working outside at that time. It was impossible to leave my mum to handle the business alone, so I promised to take over the shop and run.” And so she has, to this day.

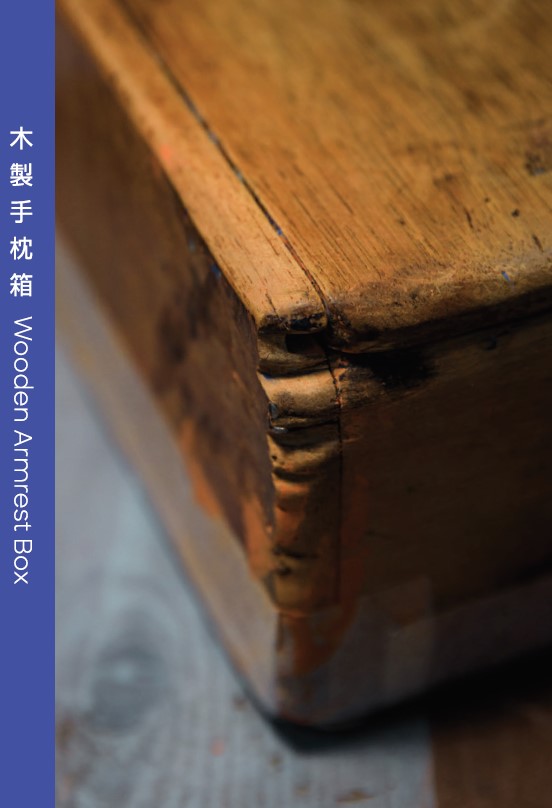

At “Kam Fat”, apart from Sister Mai’s obvious hand-carving skills, the tools in her hands are also cleverly designed. In addition to the large engraving drill for the “Dot” tiles, there are also smaller engraving knives for the “Character”, “Bamboo” and “White” tiles. These metal tools have been used for decades, and the smoothed handles have a warm and friendly feel. It is worth mentioning her box lamp, which is a great example of the craftsman’s wisdom and has a wide range of uses. “I call it the ‘magic lamp’. The small wooden box is not only used for illumination, but also for speeding up the drying of the freshly coloured paint; on top of the box is a piece of iron that can warm up blank tiles and make them more pliable for carving.”

“It was no big deal, not a lot of blood was shed, so once I stopped bleeding, I could start working again. When you first begin carving a tile, the hardest part is looking at it and not knowing where to start. You don’t want to make a wrong cut and waste the tile.”

Ho Sau-mai - the second generation owner of "Kam Fat"

The adventures of a naughty girl in Hung Hom

In Hong Kong, the image of “Mahjong” is varied. On the one hand, playing Mahjong at home is considered a healthy family activity; but “Mahjong parlours”, where people gather to play mahjong, are considered a place for triads. In the old days, Hong Kong gangster films often used to depict gang fight scenes inside these Mahjong parlours. “I’d been delivering Mahjong tiles for my dad since I was a teenager,” continues Sister Mai. But was she scared to enter the Mahjong parlours? “I was a bit shy at first, and I left the parlour right after delivering the Mahjong tiles. But, actually, those working at Mahjong parlours were just like any other customer – even if I lost a tile or there was a flaw in one, they would simply ask for an exchange.”

When she was a child, Sister Mai was a playful and active girl. “I was the naughtiest among the four children in our family. My school teachers often requested to meet my parents which bothered my mum very much.” The streets and lanes of Hung Hom, and the small family business of “Kam Fat” shaped her childhood memories. “After the shop was closed, the kids slept inside the shop while my parents slept in the small attic. In the summer, we used to sleep on the street with our folding beds. It was so hot! Everyone did the same thing, so nobody found it strange.”

Sister Mai says that, although her family made a living from carving Mahjong tiles, she learned to play the game outside by herself. In the 1960s and 1970s, when the majority of the population was poor and they could not afford to buy a set of Mahjong tiles, they would come to “Kam Fat” and rent a Mahjong set with a table for a few dollars. Sister Mai and her siblings loved delivering the Mahjong sets and tables to customers. “After we delivered them, we would stand back and watch them play. After they finished, we would take back the Mahjong set and the table. What a simple life!” But Sister Mai admits she doesn’t really like playing Mahjong: “My life is already full of Mahjong. I don’t want to play it after work!”

“Kam Fat” not only gave Sister Mai a joyful childhood, but also created the opportunity for her to meet her better half. “We didn’t meet like characters in a romance novel. We were neighbours and we ‘blinked’ at each other when passing by, and then we started dating!” At this revelation, Sister Mai makes us laugh again.

The difficulty of passing on the craft

In her small “Kam Fat” shop, Sister Mai witnessed the most prosperous times of hand-carved Mahjong, in the 1970s and 1980s, and its gradual demise as it was gradually replaced by machine-carved sets. In the past, the main source of customers of “Kam Fat” had been Mahjong parlours and restaurants. “Mahjong tiles are very durable and they do not contain delicate parts. Very few people replace a whole set of Mahjong because they have “broken” them. At best, people buy a particular tile as a replacement, or a new set when they feel that the current one does no longer brings them luck. So, even in the best of times, we didn’t get very rich!”

“Since the introduction of automatic Mahjong machines in Mahjong parlours around the year 2000, a specific size of machine-made tiles have been used, which has been a big blow to our business. Besides, machine-made tiles are much cheaper and don’t take a whole week to produce.” Today, Sister Mai is one of the few remaining carvers in the industry in Hong Kong, and is regularly invited by community organisations to hold workshops to promote her craft to young people. “I welcome apprentices all the time. But many young people can only maintain enthusiasm for a moment, and after their first or second visit, they usually don’t continue.”

Although young people cannot seemingly take the time to refine the craft, they do have their own way of paying tribute to the culture of hand-carved Mahjong tiles. Inside her shop, Sister Mai displays a colourful painting on a tall cabinet, showing the layout of the shop and Sister Mai’s concentration as she carves. “That young man was so kind to keep a record of my work; he came to paint every day for a while. After some time, he gave me this painting. I was very touched by it because it wasn’t a photograph: it was a painting that he had spent a lot of time to create.” Perhaps, being a craftsman herself, Sister Mai better appreciates the young painter’s work. As she recalls this memory she speaks gently and contentedly, and has put aside her frequent laughter for a brief moment.

Please view "Story behind 'Kam Fat Mahjong'" video here:https://youtu.be/7eu6dGHo0Ts

Please view "Story behind 'Yuet Tung China Works'" video here:https://youtu.be/CmtGZeS-6v0