Hairdressing and footwear are mundane but essential parts of our everyday lives — but when they intertwine with local culture, an unexpected chemistry forms that shows yet another facet of our unique city. Oi Kwan Barbers (Oi Kwan) — a Cantonese hairdresser with a focus on serving the local community - and Sindart — an embroidered footwear shop that integrates traditional craftsmanship with local elements — are two such family-owned businesses with decades-long histories that exhibit the very essence of Hong Kong. We interviewed their two young owners, to find out how they are turning “old into new” by fusing trends with tradition.

“Oi Kwan Barbers”

Delicate work up the alley

Walking around the heart of Hong Kong’s downtown Wan Chai, one might easily miss the small, tin-covered stall of Oi Kwan Barbers on Spring Garden Lane. Less than two metres wide, its presence is proclaimed by a signboard bearing red characters on a white background and the typical red, white and green pillar of a barber shop. There is only room inside for three old-fashioned barber chairs and a galvanized iron toolbox — all decades-old gems. This is one of the last remaining Cantonese barber shops in Hong Kong, having stood in Wan Chai for over half a century.

Lau Ka-shing (Mark), is the second generation owner of Oi Kwan Barbers. Originally a photographer, he was inspired to follow in his father’s footsteps when he saw his long-standing barber shop featured in the film Falling Angels, directed by Wong Kar-wai, during a photography class. “The barber shop in the film was beautifully decorated and captivating. When I took a closer look, I realised it was my father’s shop. From that moment on, I developed a very different appreciation for it.”

Mark’s father, Master Lau, founded Oi Kwan Barbers in 1962, when Cantonese hairdressing was prevalent in Hong Kong. “My father came from Chaoshan and had learnt to cut hair in his hometown. After he came to Hong Kong by illegally crossing the sea, he worked in a barber shop - and later founded his own business in Wan Chai. He was 24 years old when he started the shop: the same age I was, when I took it over,” Mark recalls.

Prevailing Cantonese hairdressing

Master Lau’s hairdressing skills are in the Cantonese style, which emphasises efficiency and practicality — the entire “wash, cut and blow-dry” process being performed by the barber personally, typically in very basic booths located in narrow alleys or under staircases. By contrast, the equally-popular Shanghai barber shop sees the various duties divided among different members of staff.

“I learnt from my father that there was a time when Cantonese hairdressing was very popular. In those days, some foreign companies even had their own barber’s section to cut the hair of their workers in a uniform manner. The barbers in the industrial areas of Kwun Tong operated continuously 18 hours a day, catering to the women who worked in the neighbourhood – just like a ‘haircut factory’,” Mark explains.

“My dad’s Oi Kwan is a barber shop for the local community. The word ‘Kwan’ comes from his name, and ‘Oi Kwan’ means to serve and care for the community.” Mark explains that in the 60s to 80s, the Cantonese barber shop was like a small community centre, offering local and Japanese comics such as Old Master Q and Mazinger Z to children to relieve their boredom, and attracting the elderly to gather for a smoke and a chat, while blue-collar workers would exchange market information and look for jobs while waiting for their hair to be cut. “It was my father’s wish to help keep the community together through his craft, and by running this small family business.”

“In the 60s to 80s, the Cantonese barber shop was like a small community centre, offering comics to children to relieve their boredom, while blue-collar workers would exchange market information and look for jobs while waiting for their hair to be cut. ”

The father and son barber

Mark recalls that his and his two brothers’ hair was cut by his father every five days, from the time they were a month old, so it never stayed long enough to grow. However, as his father grew older and his health deteriorated, Mark decided to put his camera down and learn how to cut hair, to carry on the family business. But his father was adamantly opposed:

“My father always said, ‘become a beggar rather than a barber’, fearing that people would look down on us, so he didn’t want the next generation to follow the same path.” Since his father was determined not to encourage him, Mark asked the other barbers in the shop to teach him the necessary skills. When Master Lau saw the other staff teaching Mark, he decided there was no need for his son to seek advice from others, when he himself was a master teacher; so he finally relented and agreed to teach Mark. “This was the trick I used to persuade him to teach me!” Mark says, with a grin.

Although Oi Kwan is small, Mark’s haircutting skills are the best of all the masters in the shop; and he has also inherited his father's and other masters’ professional way of serving customers. “I always wear light-coloured, simple shirts for work, so my customers' hair looks more distinctive. I don’t get tattoos or smoke either, as the older generation always think that these habits tarnish the professional image. And I don’t drink coffee or tea before work either, to prevent my hands shaking. I can’t afford to make a single slip when using a razor on my customer’s head.” Mark says.

Talking about the lively atmosphere in the shop, Mark could not help but remember his late father. “Even though he was suffering from health problems in his later years, he still insisted on opening the door on time every day. Even on the afternoon of the day he died, he was still in the shop cutting hair as usual; that same night, he was lying in the hospital. I think working to the last minute and, collapsing where you work, are signs of respect for your profession and craftsmanship,” Mark says, with a stifled sob.

“I think working to the last minute and, collapsing where you work, are signs of respect for your profession and craftsmanship.”

Every job is an art when done to perfection

Since Mark took over in 2014, Oi Kwan has focused on men’s haircutting and only offers a few basic styles for customers to choose from. “Don’t think it’s easy: men are looking for a more delicate touch nowadays, and are more demanding than women.” Apart from a simple haircut, Oi Kwan also offers a full range of services including washing, cutting, blow-drying, applying hair wax, ear-cleaning, shaving and facial hair removal, all of which takes up to two hours. “The most intensive part is the shaving, which starts with a pre-shave oil, a gentle massage and a warm towel for a few minutes to open up the pores and soften the roots. Next, we apply soap and lather and gently shave with a razor. It’s a real treat when the barber can handle it properly and make the customer feel comfortable and relaxed,” says Mark.

Having worked with a wide range of customers, Mark has a good understanding of their skin, bone structure and facial features. “Many people don’t know what their skull looks like. People have different skull structures: foreigners have well-defined skulls, while Chinese people have smaller ones, and their occipital bones can be different heights on the left and right. They are also more prone to hair loss which shows as an M-shaped hairline or thinning on top.” Mark continues: “I’ve had customers come in with pictures of celebrities and ask me to do the same hair cut for them. Of course it’s technically possible, but the results vary from person to person,” Mark adds with a wink and a smile. He always remembers to put himself in his customers’ shoes when he cuts their hair, using his expertise to accentuate the good and hide the bad; there is nothing cookie-cutter about hair styles.

Retaining customers

With two generations of father and son having successfully served three generations of customers, Mark believes the key is to put heart into the job. “It’s a family business that depends on word of mouth, and you have to cut with your heart to make it last. We have accumulated a lot of repeat customers over the years, thanks to our good reputation.” The shop now caters to local customers who are around 40 years old, and sometimes Mark is also asked to shave the hair of newborn babies. In addition, as Wan Chai is a tourist area as well as a commercial centre, many dignitaries and even the most powerful people in the city come to enjoy their services. Hong Kong’s “King of Gamblers”, Yip Hon, was one of his father’s regular customers, and once asked his father to come to his home to cut his hair.

With more media coverage and the advent of social media platforms in recent years, many foreign customers are visiting the shop; before the pandemic, European, American and Japanese customers had come to account for about 30% of the business. Watching Mark greeting foreign customers in English with ease, it was hard to believe that he was self-taught: “I knew I wasn’t really capable of studying, I even failed in English in public exams, so I had to learn on my own after taking over the business.” Mark also knows a little Japanese: “At first, I learned Japanese just to try to date a Japanese girl, although that failed. I never thought it would be good for business later on!”

Along with professional skills and a sincere attitude, Mark believes a good barber also needs to make customers feel relaxed and at ease by chatting with them. Sometimes, with a little observation, a barber can understand a customer’s needs from the health of their hair, even without words. “During the pandemic, a regular customer came in for a haircut with a worried face. I combed through the hair on top of his head and noticed a condition known as Alopecia Areata, which usually happens when one is under a lot of stress. I learned during our chat that he had recently lost his job. I didn’t say anything but, at the checkout, I gave him a discount. He immediately burst into tears and expressed his gratitude.”

People have different skull structures: foreigners have well-defined skulls, while Chinese people have smaller ones, and their occipital bones can be different heights on the left and right. They are also more prone to hair loss which shows as an M-shaped hairline or thinning on top.

Keeping the old, welcoming the new

While the tradition of Cantonese hairdressing has been preserved, Mark is also actively improving his service and introducing new products to keep up with the times. For example, he has put more emphasis on the hygiene of tools than his father’s generation: towels are nowadays washed and all equipment is disinfected after every use; hair care products such as waxes, shampoos and combs are available for purchase; and appointments are provided to save customers from waiting. During the pandemic, when all barber shops in Hong Kong were required to close for a period, Mark also changed his working pattern, going from door to door to cut hair for his regular customers.

Mark strives to make Oi Kwan’s hairdressing services more sophisticated and up-to-date, and he also takes the initiative to participate in various community services, including giving free haircuts to the needy and promoting traditional barber techniques to secondary school students. In recent years, he has also been training young apprentices, in the hope of passing on the Cantonese hairdressing craft. “I hope people will learn that Hong Kong has its own hairdressing culture and traditional techniques, so that foreigners will respect and appreciate them, and Hong Kong people will also feel proud of them.”

“Sindart”

The eager student becomes the teacher

Although Bowring Street in Jordan, Hong Kong, was once known as “Tailors Street”, it has now become a place for garment and grocery stalls. The hidden Bowring Shopping Mall is still home to many craftsmen, such as cheongsam tailors, alteration masters…and Wong Ka-lam (Miru), a young embroidery shoemaker in her 90s, who is the third generation owner of the Sindart.

Established in 1958, the shop was originally named after its founder, Wong Tat-wing, adopting the Chinese proverb “The eager student becomes the teacher”. Miru recalls: “In my grandfather’s time, Sindart was a “staircase shop” (so called as it usually a tiny shop under staircase) selling embroidered shoes and miscellaneous goods such as luggage and umbrellas for the local community.” Hand-made embroidered shoes not only supported a family, but have also linked three generations.

A pair of shoes that links three generations

Embroidered shoes were first introduced to Hong Kong in the 1950s by Shanghainese merchant families; their styles have constantly evolved over time. The shoes are unique in that they incorporate traditional Chinese embroidery techniques, and their different styles and patterns portray the status of the wearer. Miru’s grandfather worked in the transport and retail industries in his younger days, learning embroidery and shoe making from Shanghainese masters, before setting up his own business.

During the early days of the business, the shop was mainly used as a sales point, managed by Uncle Chung, while Miru’s grandmother and some workers who were skilled in embroidery and dressmaking, were crammed into the small workshop to make shoes. Miru’s grandfather worked both in the shop and the workshop. They worked with their hands in this way for decades. As Miru had been living with her grandparents since she was a child, she was influenced by them and became interested in embroidered shoes.

Miru smiles as she holds up a pair of exquisite “Tiger-head” shoes, saying: “When I was a baby in arms, my grandmother put these cloth ‘Tiger-head’ shoes on me, signifying to be as strong as a little tiger, to avoid evil spirits and keep safe, and to explore the world with embroidered shoes. Since I was a child, I have always worn my grandfather’s embroidered shoes. Whenever a new pattern or product was introduced, our family would be the first to try it on as guinea pigs!”

“The shoes are unique in that they incorporate traditional Chinese embroidery techniques, and their different styles and patterns portray the status of the wearer. ”

Embroiderer in the making

Miru’s embroidered shoes have walked with her through the different stages of her life. “When I was in primary school, I learned embroidery from my grandma, following her step by step.” When Miru went to secondary school, she regularly spent time in workshops learning from her grandfather how to make shoes, while at university she studied Visual Communication Design, which is related to craftsmanship, and took embroidered shoes as the research topic for her graduation paper. In the course of her research, she discovered that there was still plenty of room for development in this traditional industry and was inspired to take over the family business.

At the same time, her grandfather, who used to handle everything himself, was becoming less healthy. He couldn’t walk up and down the stairs with his ageing knees and couldn’t lift the shop shutters even using both hands. Miru’s father therefore stepped in to take charge of the shop, while Miru joined full-time to make the embroidered shoes.

Products to suit every occasion and customer

Embroidered shoes were originally a luxury item for the upper class during the Republican period. A splendid cheongsam, paired with custom-made embroidered shoes, was a symbol of the nobility’s taste and status, while ordinary people only had the opportunity to wear embroidered shoes during wedding ceremonies, symbolising a new chapter in their lives.

“My grandfather used to work in a shoe factory and noticed that the women workers only wore plain and simple cloth shoes, so he had the idea of creating embroidered shoes that were affordable for the masses by using affordable materials.” Miru recalls how her grandfather started the business. In response to the popularity of Western culture in the 1950s to 1960s, Miru’s grandfather introduced high-heeled embroidered shoes, followed by house slippers made from lace, silk, brocade and nylon, which were less commonly used in embroidered shoes at the time. A new market was successfully opened up as a result of the affordable prices.

“However, when it comes to my generation, the trend has changed and it is rare to see young people wearing embroidered shoes on the streets.” Miru has responded to this trend by creating embroidered shoes that can be worn both indoors and outdoors, for different occasions. In addition to house slippers, there are also flats, high heels, dance shoes and ankle boots.

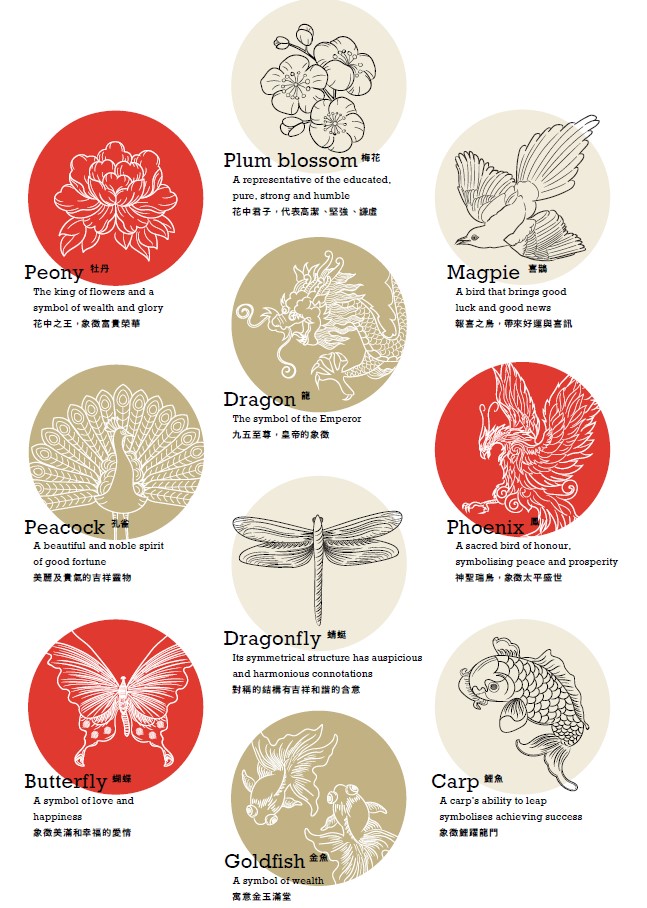

Low-cost materials such as denim and linen are used, along with more durable and improved materials such as nylon and coloured threads. As for the colours and patterns, the traditional red and black combination and use of brocade and gold thread — popular with Western customers — were retained; while silver, grey, blue, green and Tiffany blue — the favourite colours of young ladies — are also used as main colours. In addition to the common wedding motifs of peony, dragon and phoenix, goldfish and other traditional patterns of flowers, birds and beasts, modern and cartoon designs (such as cherry blossoms, owls, fruits and pandas, which are popular with Japanese tourists), have also been introduced in recent years.

In addition to expanding their market to include young people, they also cater to the needs of older customers. “Many of our regular customers are getting older and have trouble walking, so I have added soft padding and a deeply-patterned, non-slip rubber sole to improve wearability and make it easier for the elderly to wear the shoes outdoors,” explains Miru.

“In addition to the common wedding motifs of peony, dragon and phoenix, goldfish and other traditional patterns of flowers, birds and beasts, modern and cartoon designs (such as cherry blossoms, owls, fruits and pandas, which are popular with Japanese tourists), have also been introduced in recent years.”

Every step counts

The colourful embroidered shoes, which combine delicate shoemaking and embroidery techniques, are a delightful work of art to hold. Miru says that, since the embroidered shoes in Hong Kong originate from Shanghai in the Jiangsu region, hand-made embroidered shoes are now commonly made in the “Suzhou embroidery” style, with more detailed and realistic patterns. These are embroidered on fabric with needles and coloured threads. There is also a mix of “Guangdong embroidery” styles, using threads, as well as sequins and beads to enrich the texture of the patterns.

A pair of embroidered shoes can take several days to produce, and it is common to make them in batches over several weeks to save time. “To make a pair of embroidered shoes, great painting skills are essential,” continues Miru. Because of the importance of symmetry, the shoe is first sketched out, then the pattern is cut out and sketched over the fabric, and the bamboo embroidery hoop is applied to flatten the fabric before embroidery and beading begins. After embroidering the surface of the shoe, a sewing machine is used to sew up the inner fabrics, and wrap the edges. Then the semi-finished shoes are carefully contoured. The final, and somewhat surprising, step is to put the shoes into a special oven and bake them at a high temperature for a few hours to set the shape. After cooling, the embroidered shoes are finished.

Putting yourself in others’ shoes

In addition to pre-made shoes and patterns, many customers now order custom embroidery patterns, such as embroidered wedding shoes with the couple’s surnames. Miru has also met many customers who have unusual foot shapes and want to order special shoes to fit. “If a customer has two feet of different lengths, a different heel will be made to suit their needs; if they have relatively large foot bones, a wide shoe last (a model shaped like a foot) will be used; if they have flat feet, a cushioned arch will be added to the bottom of the shoe to support the arch of the foot and make it more comfortable for them to walk; if they have one big foot and one small foot, different sizes of shoes will be made for each.” The spirit of the craftsman is to understand the special needs of each customer, and literally “put yourself in others’ shoes”.

Miru recalls: “My grandfather once met a customer who had a curved foot due to a foot-binding (the now-abandoned ancient Chinese custom of tightly binding the feet of young girls in order to restrict their growth) as a result of which she was unable to wear normal sized shoes. She loved the embroidered shoes he made, but they didn’t fit her size. So my grandfather made some embroidered shoes close to the size of a children’s shoe and placed them in the shop, waiting for her to come back. The lady did come back afterwards! She took the shoes made just for her and became a regular customer.” She continues, “Although my grandfather has left us for good, some of his customers still come back from time to time to buy shoes and try them on, while sharing a lot of stories about him with me.”

Having moved from a staircase shop to an upstairs shop, Sindart has now entered the age of internet shopping, and is keeping up with the times by promoting and selling its products on online platforms. Miru is also committed to promoting the traditional art of embroidered shoes through community exhibitions and talks, and in recent years has been running workshops to take on apprentices. “Don’t think that only girls are passionate about embroidered shoes; I have many male apprentices too. I will teach anyone, male or female, young or old, who is willing to learn, in the hope of developing this art and passing on my grandfather’s craft!” declares Miru.