Flavours of Hong Kong are not just about culinary delights and beautiful scenery, but also about the work of its traditional craftsmen. In the 1940s and 1950s, experienced tailors from Shanghai moved to Hong Kong, making a new home in this city to display their enviable craftsmanship. Local Cantonese tailors vied with the Shanghainese tailors in those early days, demonstrating their own impressive skills. Over the decades, they have witnessed the changes in this city, while customers have come and gone. What remains unchanged is their persistent dedication to their craft, and their respect and concern for their customers. In this issue, we have interviewed Leung Long-kong, a 90-year-old tailor who makes qipao (traditional one piece Chinese female dress) including those worn in the film In the Mood for Love; and Tony Wong, the third generation of a Shanghainese tailoring family. Tony is passionately interested in the art of making suits, and loves to make friends with customers, and listen to their stories about this century-old craft. For tailoring is all about understanding each unique customer.

“Long Kong Ladies’ Tailors”

The 70 years’ experience of a Cantonese tailor

Long Kong Ladies’ Tailors is tucked away in an upstairs shop within an industrial building in Kwun Tong. The business has built an outstanding reputation for the quality of its work. And, despite its hidden location, both young and more mature ladies from all walks of life — and from Japan, Taiwan and Singapore, as well as Hong Kong — continue to come there to buy a well-cut qipao.

Tailor Leung Long-kong has run Long Kong Ladies’ Tailors for almost 70 years; he is now 90 years old and still a full-time craftsman. He works from 10am to 5pm, Monday to Saturday, and completes the measuring, cutting, stitching, piping, ironing, and fitting all on his own.

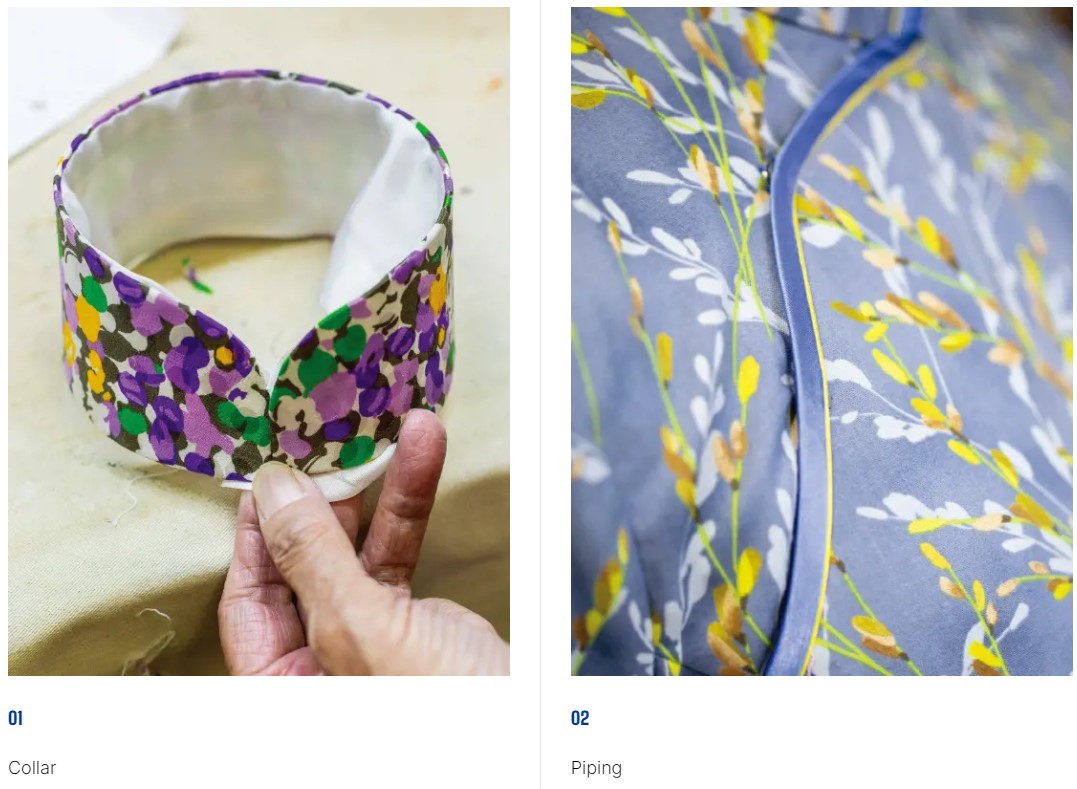

“Nowadays I only make a few qipaos a month. I am getting older, so let’s take it slowly,” Leung says unhurriedly. However, he comes alive at his workbench: wearing a thimble on his middle finger, he picks up the tailor’s scissors, and the blade skilfully cuts through the imported silk. With starching and ironing, the qipao collar is finished in less than a half day. From measuring and fitting, to handing over the finished qipao to customers, takes two to three weeks.

Leung has studied the craft of tailoring for a lifetime. “I have never made a career change in my life, I made my whole living from tailoring clothes.” He learned tailoring from a master at the age of 14, and has specialised in women’s fashion ever since. Leung’s connection to the qipao dates back more than 20 years to the glamorous movie, In the Mood for Love.

“He learned tailoring from a master at the age of 14, and has specialised in women’s fashion ever since. Leung’s connection to the qipao dates back more than 20 years to the glamorous movie, In the Mood for Love.”

Straight, smooth, fit, natural

It was around the late 1990s when the film’s famous art director William Chang Suk-ping approached him, Long Kong Ladies’ Tailors had already been established for more than 40 years, located in bustling Causeway Bay, with a ground floor shop and upstairs factory. There were apprentices to help out and he also outsourced to tailors to assist production.

When Leung learned that he was to make qipao for Maggie Cheung Man-yuk, the heroine of the film by internationally-renowned director Wong Kar-wai, he was thrilled. William Chang was responsible for sourcing the fabric, matching the colours, and designing the qipao, while Leung would oversee the measuring, cutting, and sewing. They made a great team.

Leung recalls how he went to Wong’s studio in Causeway Bay to take Maggie Cheung’s measurements, then went to the set to conduct the fitting and make some adjustments, even eating his boxed meal with the cast and crew. “Everybody knew that Wong’s films were made slowly,” says Leung. In the Mood for Love was filmed for two years, while Leung also took two years to finish those qipaos. The film was eventually released in 2000, and the 23 distinctive qipaos were worn by character Su Li-zhen, played by Maggie Cheung. The flowing curves and different patterns were enchanting, and created a trend for qipao.

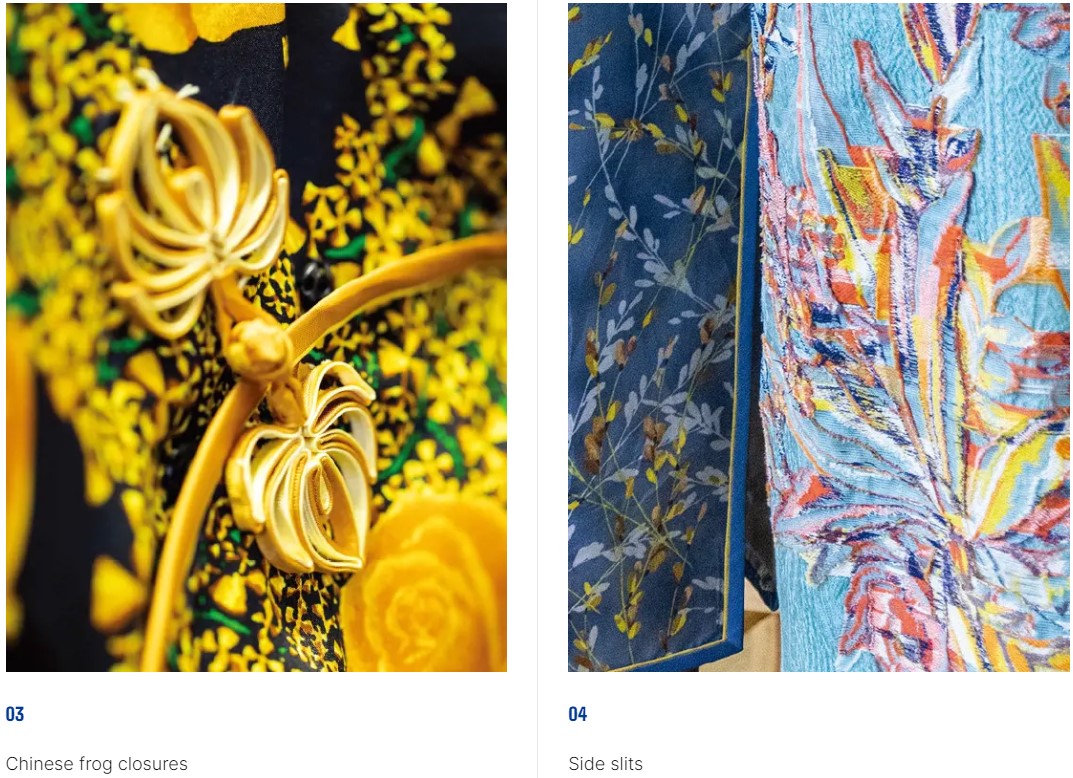

The origin of the qipao can be traced back to the 1920s, when women from the Republic of China were pushing for gender equality and wanted to wear clothes on a par with men’s. They borrowed the design of the robes worn by Manchu women, and thus developed the qipao, also known as the cheongsam. In the early 20th century, wearing the qipao was generally the preserve of young women from good families, and celebrities. The early qipao was relatively loose; then, in the 1950s under the influence of western culture, slim-fit and three-dimensional cutting became more popular, with narrowing waists that showed off the beauty of women’s bodies. At the same time, details like Chinese frog closures, side slits, and narrow hems were added, heralding the golden age of the qipao.

“The most important thing about the qipao is to ensure it fits perfectly. From shoulder, chest and waist to the slit, it must fit without a single crease.”

Leung explains that the most important thing about the qipao is to ensure it fits perfectly. From shoulder, chest and waist to the slit, it must fit without a single crease. “The slit is the most important; if it is not well-made, it will lift up, and will not be naturally straight,” says Leung.

This may sound simple, but achieving it takes decades of experience. The traditional qipao is rarely made of stretch fabric — cotton and silk are mostly used; therefore, the size must be very accurate. Taking body measurements is a key process, and the neck, waist, chest, arm and so on must all be measured carefully. Then the pattern is drafted and cut it out.

Everyone’s body is three-dimensional and unique. Just relying on cutting is not enough; it is necessary to starch the fabric to shape it, with skilful ironing to create a curved waistline, and sewing in a stiff band to fix the curve and maintain its perfect shape.

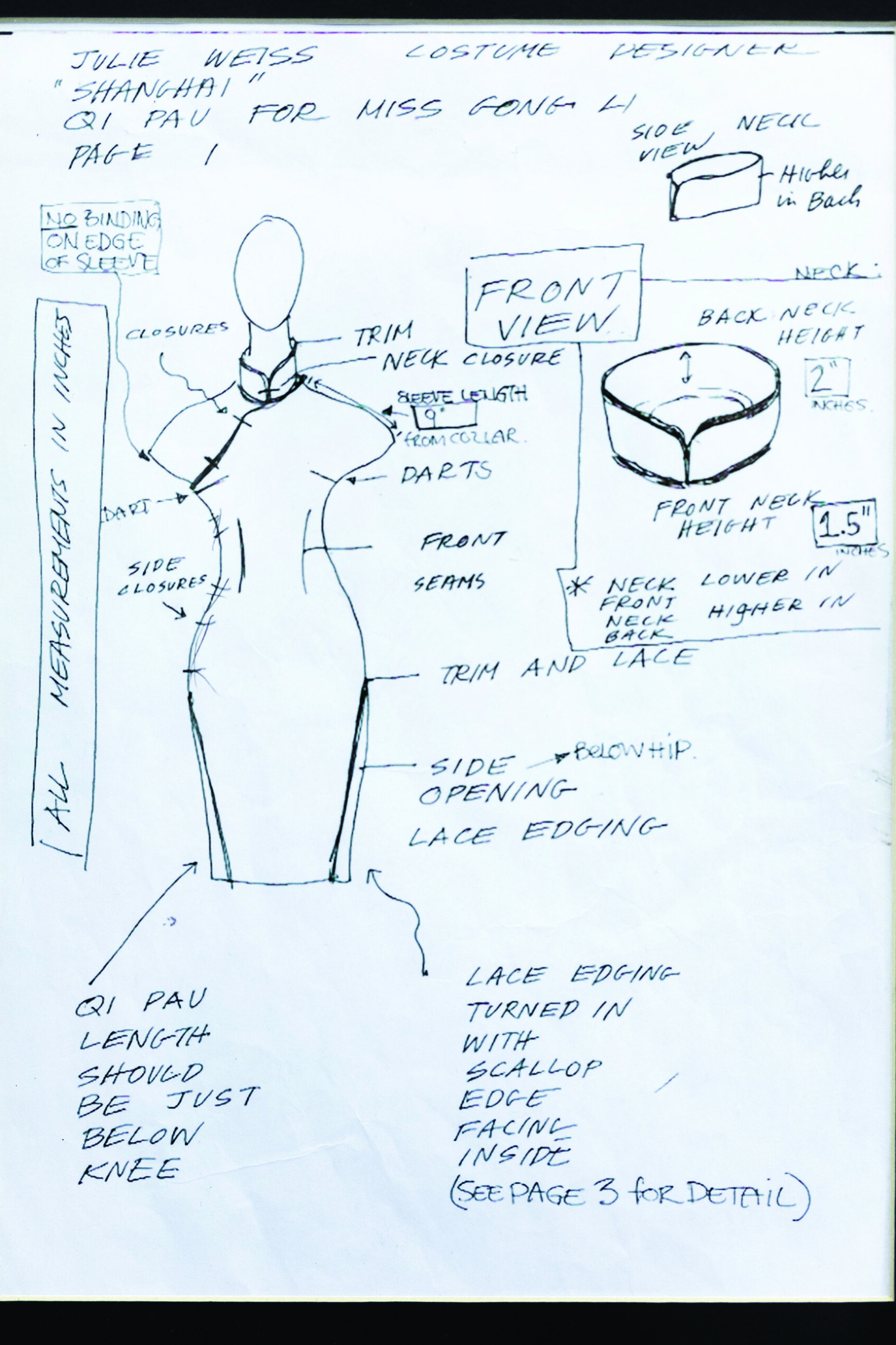

“In the past, the qipao collar was short. We designed a higher collar when In the Mood for Love was filmed, which started a trend,” adds Leung. Later he made qipao for Zhang Ziyi in the film 2046 (another film by Wong Kar-wai), and Gong Li in the American film Shanghai — all of which adopted the high collar design.

“In the past, the qipao collar was short. We designed a higher collar when In the Mood for Love was filmed, which started a trend.”

Getting a foothold with his craft

Hong Kong tailors have always been renowned for their craft. Traditionally, they can be divided into Shanghai-style and Canton-style, and Leung belongs to the latter. The Shanghainese tailors value their needlework, ensuring the threads are not easily spotted on the clothes; while the Cantonese tailors focus on sewing techniques, using machines to sew the fabric or zipper, which may leave visible threads on the surface of the cloth.

In 1946, the Chinese Civil War was still raging. In order to make a living, Leung followed his relatives to Hong Kong from his hometown of Foshan, Guangdong, at the age of 14. He went to Central as soon as he arrived, to learn from his distant relative who was a tailor. He was made to do all the menial chores well, on his way to learning the tailoring skills of cutting and sewing, which took three years. After working there for several years, in 1958 he started his own business in Causeway Bay at the age of 26. He had had a foothold in the area for over 50 years.

Hong Kong’s economy began to develop, and the entertainment, film and television industries were growing as well. Young local women were starting their careers, while upper class wives had to attend various banquets. The mass-produced ready-made garment industry was not yet well developed, and those who had spare money would have their clothes made by bespoke tailors. There were many tailor shops in Causeway Bay and Happy Valley, where tailors from Shanghai also settled, making for a vibrant scene. Leung specialised in women’s fashion, tailoring dresses for office ladies, clothes for television and radio presenters, hostesses in high-end nightclubs, and evening gowns for the Miss Hong Kong Pageant.

“The hostesses from Tonnochy Ballroom and Ritz Night Club in North Point (famous high-end nightclubs in Hong Kong) were my customers,” Leung recalls. Back in the 1960s and 1970s, Saturday was the busiest day of the week. People came to order their clothes, and some came to collect bespoke coats to match their qipaos, for leading the winning horse at the racecourse. “Some ladies went to watch the horse racing, and it was popular to wear the qipao with a coat.”

At the peak of his business, Leung had eight apprentices, outsourced to more than a dozen tailors, and had domestic workers to cook and do the cleaning. In his early 30s, Leung got married; then his wife took care of the family, and he raised four children funded by his craftsmanship.

The world was changing rapidly, and the ready-made clothing industry matured quickly, with the emergence of chain fashion stores and fast fashion. Back in the 1990s, Leung already felt the cost of bespoke clothes was becoming too high, that he could not keep up with the production rates of the garment factories, and that his business was accordingly not as good as before. After participating in the production of In the Mood for Love, he shifted the focus of his business to qipao, making something “unique and special”.

In the Mood for Love was a real hit and, even years after the film’s release, many customers kept coming, and the business was overwhelming.

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, Saturday was the busiest day of the week. People came to order their clothes, and some came to collect bespoke coats to match their qipaos, for leading the winning horse at the racecourse.

The piping is like a frame for a famous painting, highlighting the pattern of the qipao and adding to its elegance.

Legends never retire

Leung does not go for glitz and glamour: “The best thing is to see customers wearing a qipao that fits well and is comfortable.” Leung says he must personally make the qipao for each customer, whether they are a superstar or an ordinary customer.

Nowadays, there are shops selling off-the-peg qipaos in various standard sizes. To better fit different body shapes, they are often made from stretch fabric, and a zipper is added at the back to make it easier to control the cut and the straightness of the slits. Some buttons are also added at the front, but only for decoration. Leung always feels that a hand-made qipao is incomparable.

The bespoke qipao, no matter the collar, chest, or waistline, fits naturally with the human body, and will not feel tight when moving. Leung is proud of his piping skills: choosing silk according to the colours of the fabric, sewing piping less than half centimetre wide around the collar, cuffs and hem, and then starching the qipao carefully, ensuring that the width of the piping is always the same — straight and smooth. The piping is like a frame for a famous painting, highlighting the pattern of the qipao and adding to its elegance.

About ten years ago, the old shop in Causeway Bay was sold. Leung was 80 years of age that year, and so he talked about retirement, but he was as diligent as any office worker. So he eventually moved to Kwun Tong, closer to his home, and rented a shop to start his business over again.

Some of his eight apprentices set up their own garment factory on the Mainland, some retired, some changed careers, and some passed away. But Leung decided to do it all by himself, making each qipao slowly, stitch by stitch.

His four children are all pursuing their own careers, none of them in the fashion industry. They now provide logistical support for their father, including translation and handling media interviews. His grandchildren who live overseas also play a part, helping him to maintain a social media presence, so that more youngsters can learn about tailoring and understand the qipao.

Interestingly, more and more young people have come to Long Kong Ladies’ Tailors for tailor-made qipao in recent years, while some old customers have introduced their friends as well. “Maggie Cheung came here a week or two ago and referred her friend to order a qipao here.” Leung says.

We interviewed Leung on the Saturday when Hong Kong hoisted its first rainstorm signal of 2023. Would Leung be working today? When we opened the door, Leung was already there, ironing on the workbench. A few days ago, this garment had been nothing more than a pattern; now, it is finished and hangs elegantly on the wall, with the silk coming alive.

“Fu Shing & Sons”

The secret of old Shanghainese tailors

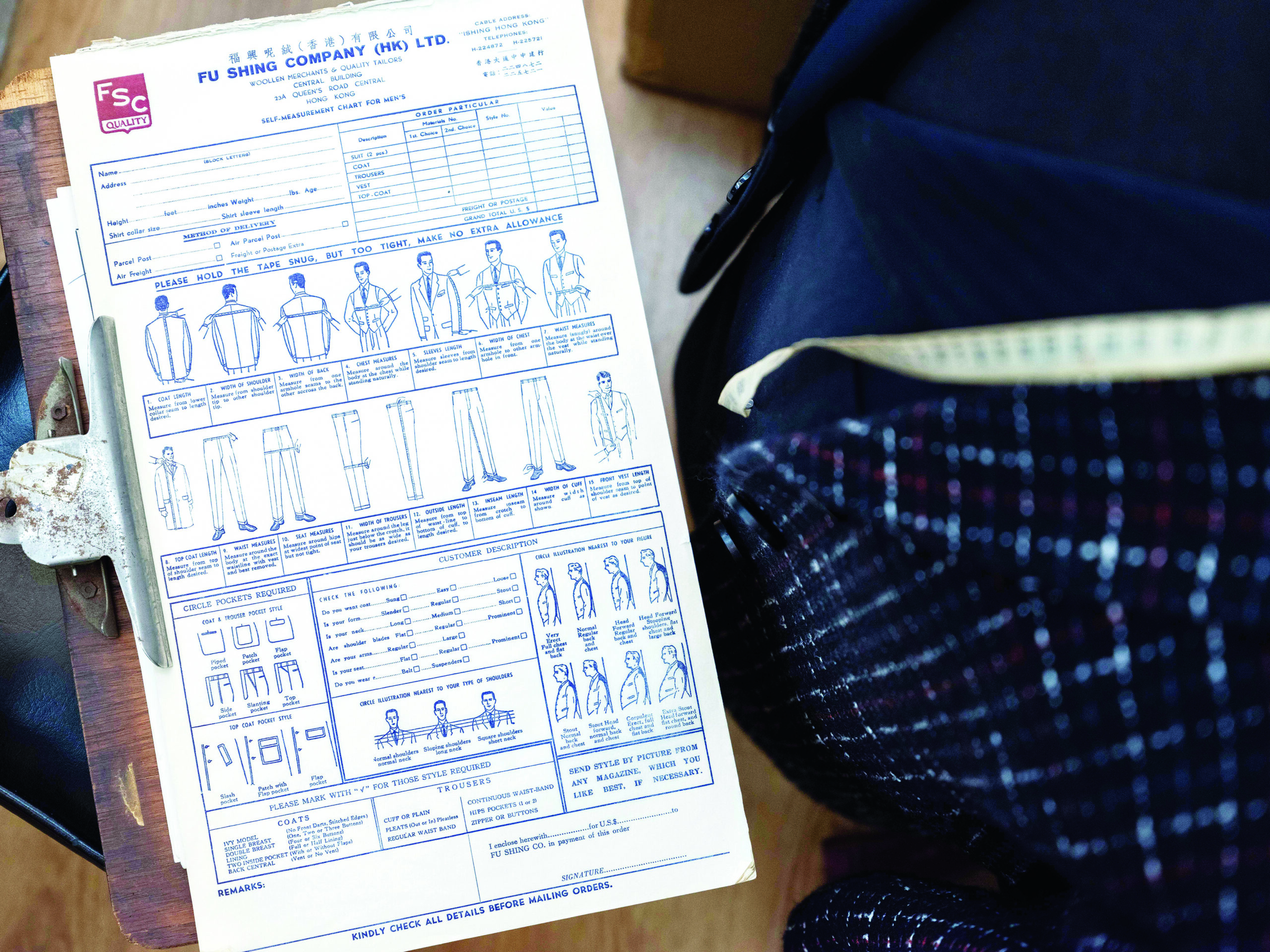

Fu Shing & Sons (Fu Shing) is a suit tailoring shop, and also a miniature museum. The phonograph, iron and wooden rulers still in use in the shop are all antiques, and the suits hanging all around have their own stories to tell. Tony Wong, the 72-year-old owner and tailor is a tubby man, with a big smile on his face. He casually puts a soft yellowish tape around his neck and begins an endless talk on the art of suit making.

“Everyone’s proportions are different. Each tailor has their own way of cutting. Some tailors are good at making suits for hunchbacked customers, while some are great at making suits for customers with ‘pigeon chest’ (when the chest is pushed outward abnormally). The tailor will find his own way of cutting to flatter the customer,” Tony proudly begins, in this upstairs shop hidden in Central. “Suits are about how to ‘cover up’, and make people look nice — that is the art of the suit.”

Whether the unique way of cutting or the art of “cover up”, successful suit making depends on the experience and skills of the old craftsmen. Tony randomly picks up a red suit in the shop and says, “This is made for an African customer: his chest is broad, so a nice curve needs to be created in the front.” He turns to take another suit and explains, “This is a sample made for some Middle Eastern customers, which is full-canvassed; it is very hard to find this kind of craftmanship nowadays.” The canvas is sewn between the outer fabric and lining to provide structure. The canvas is pad-stitched to the jacket slowly by hand and takes a lot of time and effort. A full-canvassed suit means the entire suit jacket has an interlining of canvas.

Do the old customers still stop by? His finger points upwards, indicating that some customers have already passed away, and then opens a thick file folder containing photos of his father and grandfather, and old documents. One of these, dating back to 1927, recounts the history of this Shanghainese tailor family, who originated from a time-honoured brand of Shanghainese tailor shop, “Loa Hai Shing”. In this year, a United States Navy ship that docked in Shanghai, gave permission to this tailor shop to come aboard and provide bespoke services.

“Suits are about how to ‘cover up’, and make people look nice — that is the art of the suit.”

Experienced and knowledgeable

In the 1920s, Shanghai was known as “Paris of the East”, attracting many visitors from different parts of the world. Tony says his father James Wang, was the second generation of Loa Hai Shing, established in 1902 in Shanghai. “My family ran a fabric import business in Shanghai, mostly worsted and woollen. We had tailors with us to make suits.” With a large family and fierce competition, his father felt it was difficult to gain a foothold in the Shanghai market, so he moved to Hong Kong with Tony’s mother and set up Fu Shing in Central in 1948. A year later, Loa Hai Shing also officially moved to Hong Kong, using the original brand name.

In those years, with war and political change, many Shanghainese fled to Hong Kong, including wealthy industrialists and skilled tailors. They shared the market with Cantonese tailors who had long been rooted in Hong Kong. Tailor shops began to flourish, with everyone showcasing their unique crafts to build their own clientele.

Tony says his father was fluent in English, and with the network and knowledge accumulated in Shanghai, he soon developed a clientele of American soldiers, lawyers, and bankers. In 1958, the Central Building was completed in Central, and Fu Shing moved to a spacious rented ground floor shop with an extensive cellar. The cellar stored fabric and had workbenches for tailors, while customers were served in the ground floor shop.

As the years passed, the spotlight shifted from Shanghai to Hong Kong, as European and American capitalists came to Hong Kong to make their fortunes. Large foreign corporations set up factories and branch offices in Hong Kong, and Fu Shing had arrived in the heyday of Central, with many bosses of foreign companies, senior managers and bankers coming to order suits. As the Cold War continued, Hong Kong became the middle ground where American, British, and other countries’ warships and aircraft carriers could berth freely. The naval officers never forgot to order a nice suit during their four to five days rest in Hong Kong.

The naval officers never forgot to order a nice suit during their four to five days rest in Hong Kong.

Suits originated from the Western military uniforms. Were Chinese tailors familiar with the Western styles? Tony says that like the generation of his father, the old Shanghainese tailors had a global perspective, and used to serve customers from different countries and cultural backgrounds.

“There were various concessions in Shanghai. Each tailor created clothes differently in each concession, and learned about the body shapes of different people around the world. Why are Shanghainese tailors so skilled? Because they are experienced and knowledgeable,” says Tony. “At the same time, many Jews fled to Shanghai to escape the Holocaust during World War II. They brought a lot of high-quality fabric and buttons after they went to Shanghai, so that Shanghai was able to keep up with the trend and was comparable to European fashion.”

Later, when a large number of Shanghainese tailors moved to Hong Kong, they brought capital, crafts and vision with them. “Shanghainese tailors made a huge impact on Hong Kong. Hong Kong people were somewhat banal, and there were a lot of British suit fabrics and fashionable designs that they had never seen before. These Shanghainese tailors brought a breath of fresh air,” says Tony.

“There were various concessions in Shanghai. Each tailor created clothes differently in each concession, and learned about the body shapes of different people around the world. Why are Shanghainese tailors so skilled? Because they are experienced and knowledgeable.”

Shanghainese craftsmanship at Hong Kong speed

Tony was born in Hong Kong in 1951. He was raised in the tailor shop, but he never felt particularly talented in the craft. “I am not a talented tailor,” Tony says. He loves making friends and exploring the world. During secondary school, his father sent him to a boarding school in Canada, and later he attended university there.

When he returned to Hong Kong during the summer breaks, he started to learn cutting and sewing from the tailor master, and often assisted at the Central store. He received the customers, and took the businessmen and navy personnel on sightseeing tours of Hong Kong. However, he never thought of entering the business. He studied economics at university and worked in a bank after graduation, until his mother called to say his father was ill and urged him to hurry back to Hong Kong.

“I returned, but my father was fine,” Tony laughs. He treasured the business of his parents, and stayed in Hong Kong to start helping out at the tailor shop in the early 1980s. He officially took over the family business in 1994.

Rents in Hong Kong soared after the economy boomed, while the ready-made suit industry matured. Tony recalls that at the time, the rent for the Central Building shop tripled. “Can you imagine how many suits we had to make to pay the rent? The rent had gone up so much that we could only surrender.”

This third generation of the old Shanghainese tailor family met the new era of challenges and opportunities. Tony gave up in Central and moved Fu Shing to the Fleet Arcade in Wan Chai, next to the Fenwick Pier, where foreign military vessels berthed. For the next 20 years, Fu Shing became known for serving the American and British navies; but, gradually, horse trainers, businessmen, lawyers, and other kinds of customer were attracted, too.

For the next 20 years, Fu Shing became known for serving the American and British navies; but, gradually, horse trainers, businessmen, lawyers, and other kinds of customer were attracted, too.

The naval vessels usually berthed in Hong Kong for four days and three nights. Tony merged the sophistication of Shanghainese style with the efficiency of Hong Kong people, and often worked overnight with several tailors to rush out suits for sailors in just three days. Once when an American naval officer was in a hurry to marry a lady that he had met in Hong Kong, Fu Shing managed to finish the suit in just one day, so that the sailor could have his wedding ceremony on time.

Tony, who is straightforward and cheerful, loves to chat with his customers even when time is tight. He takes body measurements, chooses fabric, and gets to know their professions, habits and the purpose of the suit at the same time. “Tailoring skill is only one third of making a good suit. The most important thing is to understand your customers. Being a tailor, you also need to be a psychologist. You must imagine what the customer will do with the suit, whether to impress or to look professional?” Tony says.

“Tailoring skill is only one third of making a good suit. The most important thing is to understand your customers. Being a tailor, you also need to be a psychologist.”

He continues that many American soldiers order custom suits to meet their superiors when they are promoted to civilian officers. They are not fussy about the style. But because they need to salute so often, the sleeve cuffs must be slightly longer and wider than ordinary ones, so that they do not show too much of their shirts. If they often give speeches, the colour of the fabric should be brighter. If they are professionals such as architects and doctors, grey suits are preferred to look calm and professional.

Often, Tony needs to adapt to the customers’ figures and hide their imperfections. For example, if a customer has large buttocks, he will advise him to choose the double vent suit jacket. “One of our regular customers is a horse trainer. He needs to hold the reins with one hand and the whip with the other, when riding horses. Years of such activity lead to uneven shoulders, so we add some shoulder pads to even up the shoulders,” Tony says. “I know many strange stories about our customers, and they become good friends with me over the years.”

The tailor-made suit with the human touch

Tony unintentionally became a tailor 40 years ago, but found it increasingly enjoyable. Customers always shared stories from all over the world and he learned from their life experiences.

The world is changing fast. In recent years, fewer foreign warships dock in Hong Kong and aircraft carriers have become almost extinct. The days of hundreds of people queuing to order custom suits has gone. With the demolition of Fenwick Pier and Fleet Arcade in early 2022, which marked the end of an era, Fu Shing has moved once again — to an upstairs shop in Central.

Old customers still come from time to time, and the new customer base is expanding. “Many young people like bespoke suits. Not only men order suits, but also more and more women. Unisex clothing is popular, so we use the fabric of men’s suits to make women’s suits, and the effect is nice,” Tony says. Hong Kong people are flexible and creative. Now Hong Kong has many hot days, so it’s not always necessary to wear a suit jacket, and a waistcoat can be more suitable in such weather. He also discusses the design and production with customers.

Tony believes there is a friendship between the tailors and their customers. To this day, Fu Shing maintains the tradition of “one year free-of-charge alteration service” for their bespoke garments. He saw a customer gain weight after marriage, and needed to resize the clothes; he has also observed a customer who lost weight due to illness; some customers have passed away, while others have married. Tony is there to witness all his customers’ life stages and events.

The suits that people wear for so many years, is truly tailored with the human touch.

“There is a friendship between the tailors and their customers. To this day, Fu Shing maintains the tradition of “one year free-of-charge alteration service” for their bespoke garments.”