Airfreight has a long history of moving animals, but it remains a specialised and highly-emotive commodity whose complexities and challenges lead most forwarders and many carriers to shy away from it. In this issue of Hactlink, we lift the lid on this largely unknown business:

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) reports that over 4 million pets and live animals are transported by air each year, largely because it offers a high level of welfare and safety. “Air cargo facilities are designed to maintain stable temperatures, humidity levels, and air pressure, which are critical in ensuring health and well-being during transport,” says IATA’s Global Head of Cargo, Brendan Sullivan. “Moreover, air transport is the fastest way to move live animals across long distances, reducing travel time and minimising stress.”

The animals most commonly carried by air are pets, livestock, aquatic animals, laboratory animals and exotic animals. “Domestic pets may travel by air when owners relocate or go on vacation,” adds Brendan. “Fish and other aquatic animals are often transported for aquaculture purposes. Air transport is important for breeding stock of farm animals and racing horses. Wildlife is often transported by air for the pet trade or conservation and research purposes, because air transport accesses remote locations that may be difficult or impossible by road or sea.”

Strict regulations govern live animal transport to prevent the spread of diseases, and protect animal safety and welfare. These regulations, together with State and Operator Variations, are published in the IATA Live Animals Regulations (LAR). This is updated annually to incorporate changes in regulations, and new scientific and industry recommendations. Since its introduction 50 years ago, new sections have been added covering aquatic animals, primates and reptiles, as well as new container and labelling requirements, and rules for animal transport during exceptional weather conditions. “In 1970, the LAR contained 66 pages,” continues Brendan. “Now it has more than 570 pages. The IATA LAR is continuously evolving.” Currently, the Live Animals and Perishables Board is working on companion animal welfare, live animals in-cabin, and sedation guidelines.

In 2018, IATA added Live Animals to its growing suite of CEIV accreditation programmes. CEIV Live Animals establishes baseline standards to improve competency, infrastructure and quality management in the handling and transportation of live animals. There are currently 23 certified companies: 6 airlines, 8 cargo handling facilities, 3 GHAs (ground handling agents) and 6 freight forwarders. Says Brendan: “Another 10 companies are in the process of achieving certification and, with the number of consignments of live animals increasing year on year, we expect the number of certified companies to grow respectively.”

Over 4 million pets and live animals are transported by air each year, largely because it offers a high level of welfare and safety.

Snails to elephants

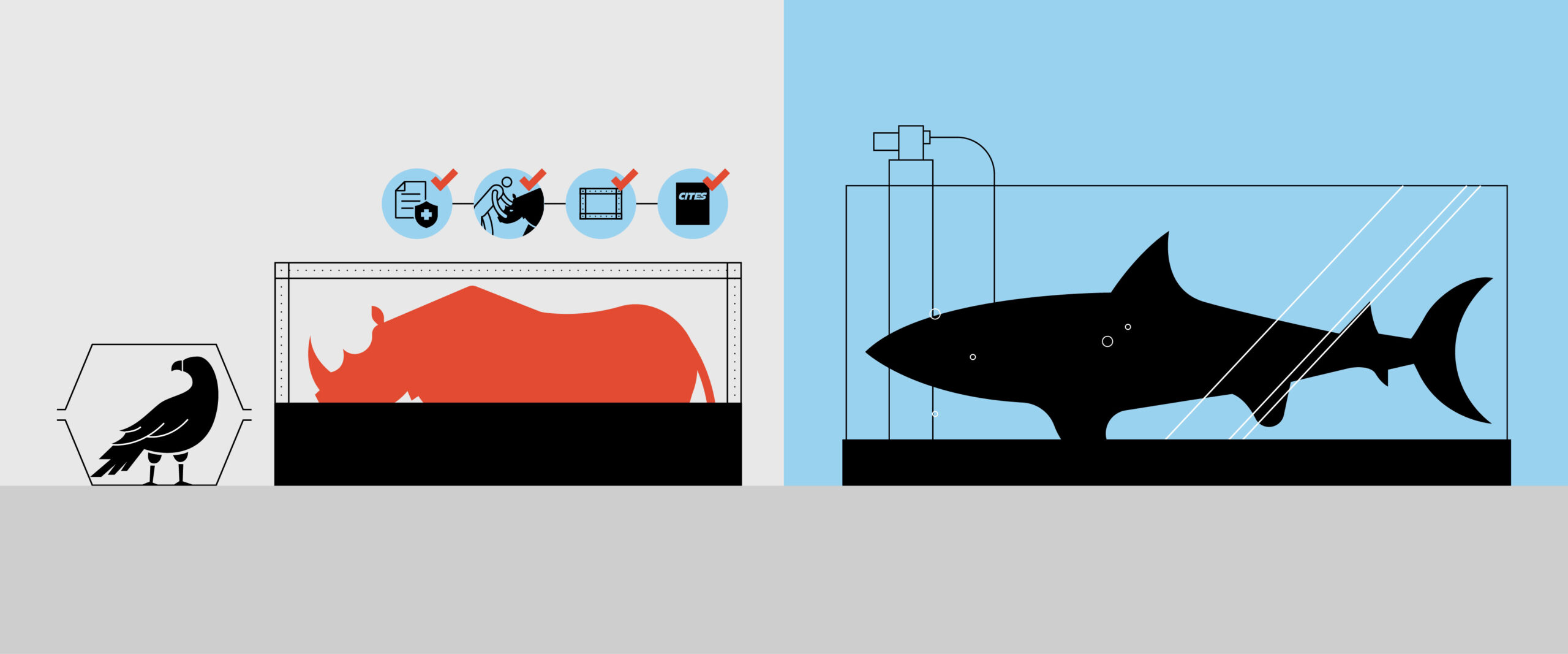

Among the select band of specialist global animal shipping companies is JCS Livestock. Based in the UK, the company has handled all kinds of live animals for all types of customers since 2000. “It could be absolutely anything,” says Michelle Brereton, the company’s Project Manager. “Snails to elephants, gorillas, tiger sharks … anything you can think of, we have probably done it!” That also includes day old chicks and ducklings, hatching eggs, and even bull semen. “A lot of falcons travel to Dubai in the falconry season, from June through to September.” Operations Director Simon Obank adds. “The falcons are for racing, and there’s a lot of paperwork to check.

“We have also moved Bermudan snails, which are being bred in the UK and shipped to Bermuda. We’ve done 2 shipments, and now they are back in their natural habitat.” Each tiny snail is individually marked to identify it, in a delicate and highly labour-intensive process.

“Among the largest animals to date have been elephants and white rhinos,” he continues. “We’ve transported sea lions including a mother and child, and sharks. There’s a lot of aquarium work.” But he is adamant that they have clear ethical policies that preclude moving animals for testing.

The market is currently a mixed picture, continues Simon: “The UK import market has suffered both because of Brexit and economic uncertainty; these have impacted the number of people moving here. If people aren’t moving, pets don’t move. And if people aren’t going on holiday and taking their pets with them, it also affects us. But when it comes to zoological and conservation movements which have been years in the planning, they are still going ahead. The commercial and conservation side is definitely a growth business.”

The preparations and processes involved in moving all animals are complex and require specialist knowledge, continues Simon: “For a rhino, we would firstly ensure that the destination country would be able to import it. We’d look at the health requirements for it to move; there might be a certain quarantine period before it leaves or when it arrives, and certain vaccinations it might need. We would advise you and your vet what you need to do to ensure the health certificate (an official government document completed by vets here in the UK) is signed off, and in the case of a rhino you would need CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) paperwork as well.

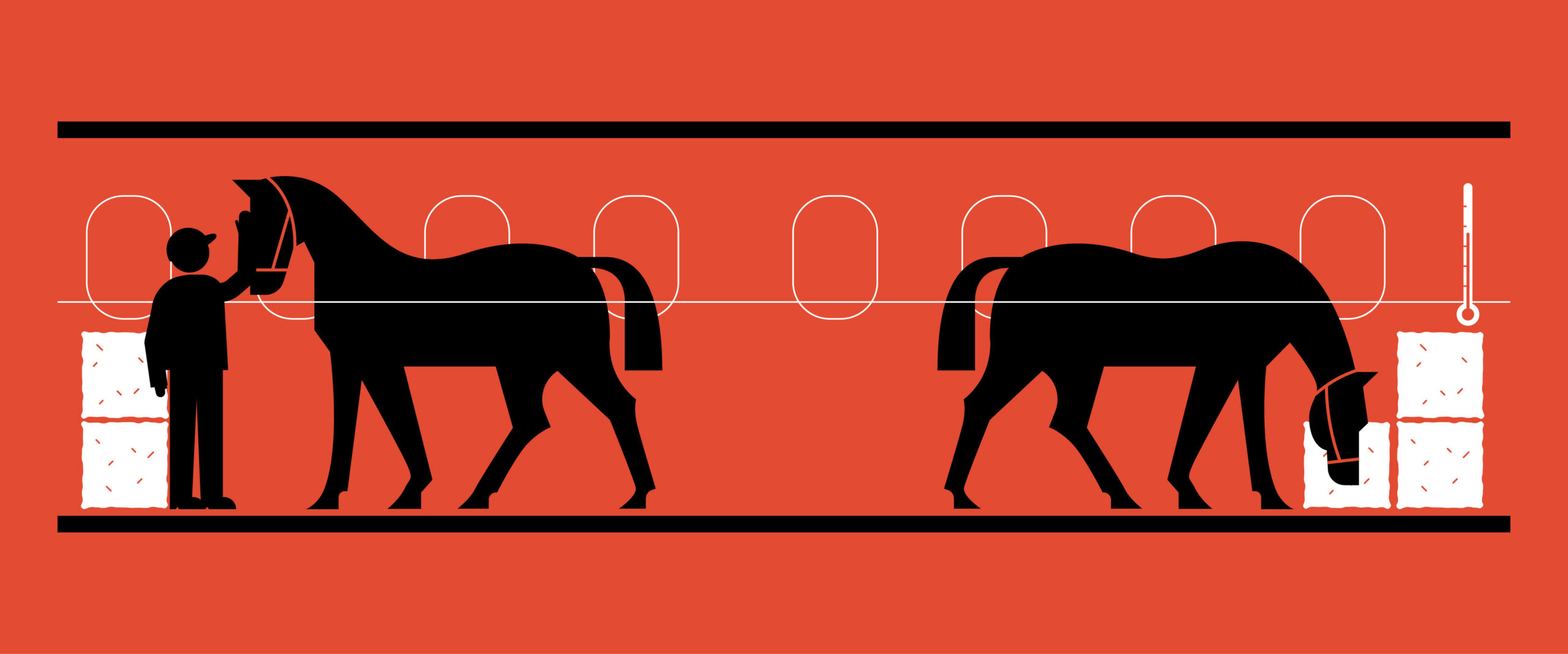

“Then we would liaise with the destination agent, because we need to know about any specific import requirements and any additional import permits involved. We would also need to organise the transport to and from the airports. With rhinos we would liaise with the airline to ensure their aircraft was large enough, that there was a suitable service available to that destination, and that they have facilities for the grooms. We would also ensure the crating requirements were met; for that type of shipment we would need a very robust custom-built container.”

“The preparations and processes involved in moving all animals are complex and require specialist knowledge.”

Welfare the priority

Although airfreight is used for its speed, does that mean animal shipments can be handled at short notice? “It depends on the destination and type of animal,” continues Michelle. “If it’s a cat or dog or destination without any special requirements, it can be turned around quickly as long as we can get space on the aircraft. But if it’s something that has more detailed requirements on the health certificate — such as time periods you have to wait between one vaccination and another — you might have to wait 6 weeks.” “A lot of the conservation work we do is 4 to 5 months in advance,” adds Simon, “because welfare is the main priority, and making sure everything goes smoothly without incident.”

Vets are involved in every shipment; for cats and dogs, JCS Livestock works with its chosen vet, so can offer customers an all-inclusive service incorporating treatments and signing off the health certificate. “For zoo animals and bigger movements, we generally work with the customer’s own vet, or provide guidance on who they can use,” says Michelle. “It has to be an official veterinarian: it can’t be just a practice vet, they have to be qualified to sign off the health certificate. We work with DEFRA (the UK’s Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs) and its offshoot APHA (Animal and Plant Health Agency) who are the governing bodies for these certificates. They always offer advice to the vets and we can liaise with them and the vets to ensure the paperwork is understood and correctly completed.”

In such a complex business, it’s perhaps surprising that there is no central source for all the information required. That’s why there is no substitute for practical experience, says Simon. “Phil Knowles, who manages the zoological side of our business, has been doing it for us for 26 years. He was one of the first people to move animals through London Heathrow. When you’re moving a pet for somebody it’s like moving one of their family: you want to be able to give them the right information, and make them feel comfortable.”

“When you’re moving a pet for somebody it’s like moving one of their family: you want to be able to give them the right information, and make them feel comfortable.”

Constantly changing

“It’s about asking the right questions, and ensuring you keep up to date … making note of changes, so you can advise customers correctly. It’s about checking with the destination whether anything has changed — especially for the big animal movements. But even for cats and dogs, the authorities can change policy all of a sudden, while airlines will change what they accept, and the routes and so on are constantly changing. You’ve got to just keep asking the questions. IATA, customs, and the airlines all have their own regulations, which we have to meet,” adds Michelle.

Simon continues: “A general forwarder doesn’t have the detailed information and experience, or understand the requirements. We have that information. When it comes to zoological moves the customer has to feel happy working with us — that we understand the requirements and have everything in place. If anything were to go wrong it would be a PR nightmare for them and us.”

In reality, so thorough are the procedures and regulations, that things almost never do go wrong, says Michelle. “But there’s occasionally something along the line, like a flight’s delayed. These are live animals — not a carpet that can wait in a warehouse for a couple of days. We always have that added pressure that their welfare is being looked after, that they’re not travelling for longer periods than necessary, and that there is a place where they can be looked after if there is a problem.

“Technically the problem rests with the handler once they’ve received the animal, but handling sheds don’t necessarily have facilities for holding animals. What we do have at LHR is the Heathrow Animal Reception Centre (HARC) which is the Border Post for LHR. If a cat misses its flight or there’s a delay, we can either arrange for HARC to go and collect it or drop it back for us to collect. The HARC is like a big cattery and kennels, and they also have facilities for horses, fish and so on. We wouldn’t want animals staying at a shed any longer than necessary. We have the facilities here to let them out and give them food and water.”

Before any animal gets onto an aircraft, it has to have fit-to-fly certification from a vet within 48 hours of departure. “If there is any reason why the vet feels the animal cannot travel, it won’t,” adds Michelle.

The route is of great importance in ensuring the safety and comfort of the animal, says Michelle: “If the animal is travelling to Singapore, for example, we prefer to take a direct flight, but for Australia you would never do that: you would have a stopover. We would never let the animal travel for that period of time; 12 to 14 hours would be the longest.

Nice touch

“We know what facilities exist on particular routes. If a stopover is involved, we may pick one carrier over another because of the facilities they have,” Michelle continues. Maintaining a dialogue with carriers is important, she says, in keeping up to date with any service changes and new facilities. “It’s important to be able to give customers that information, especially with cats and dogs, which are like their children — that, when they get to the stopover point, they’re going to be well looked after. Sometimes we even get pictures from the airline, which is a really nice touch.”

Another factor is the aircraft type being operated; not all are suitable, she continues: “If an airline cannot offer ambient temperature in its hold, then it will not accept the booking. And if it comes to the point of loading and the system fails, the animal will not be loaded.” Ground conditions also matter, she continues: “Some airlines and handlers have air-conditioned vehicles to transfer animals on the ramp, but others don’t. So, at certain times of the year if temperatures are too high or too low for boarding or unloading, they also won’t accept the booking.”

Contrary to what one might expect, animals are not sedated before a flight, says Michelle: “Sedation reduces blood pressure, and when they are travelling by air it drops again, which could be fatal; so we never, ever sedate animals. Horses and other large animals tend to travel with a groom, and if they become stressed the groom can look after them and administer medication if required. But if animals are put in the bellyhold, there is nobody to look after them and any kind of sedation could be really dangerous. All animals are certified fit to fly: although the flight can be stressful for them, it should never be so stressful that they need any kind of sedation.”

After many years of animal transportation by air, is the industry getting any better at it? Simon says it depends on the airline, and how much it values this kind of business. “As a result of COVID there is not so much international travel right now, and less pet movements; so some airlines aren’t even doing it anymore.”

Simon welcomes the creation of IATA’s CEIV Live Animals certification, and the standards it sets. He thinks its take-up will be greater if, as with pharma traffic, it becomes a must-have. “We do think it’s a good idea, absolutely. The animal’s welfare is the most important thing; that’s our business. You have to have the training, understanding and facilities to do this work properly.”