When it comes to Hong Kong’s manufacturing industry, the first thing that comes to many people’s minds is its general decline. But two 1980s artisans have bucked this trend, boldly setting up a factory in Hong Kong to distill handcrafted gins. Over the past three years, they have overcome many obstacles such as submitting licence applications, sourcing and buying specialist equipment, and battling the pandemic. With passion and tenacity, they have opened up a whole new world in Hong Kong that blends Eastern spices with Western spirits. Along the way, they encountered by chance two of Hong Kong’s last remaining coppersmiths, seniors who helped in the production of the gins by employing their nearly-extinct copper-working skills. Their collaboration is also a meeting of the Past and the Present. These representatives of two very different generations of Hong Kong people nevertheless share the belief that the most important things are to be open-minded, flexible, innovative and embrace new challenges.

A new quest at 30

Ivan Chang and Dimple Yuen remember how surprised the Customs and Excise Department was when they first asked them how to apply for a Liquor Manufacturer’s Licence: “Why do young people still want to make spirit today?” It had been many, many years since the Department had last granted such a licence.

Hong Kong people enjoy drinking alcohol, but rarely try to make it. Ivan observes that in the last 20 to 30 years, imported liquors have become more popular in Hong Kong: brandy, red and white wines, whisky and, in recent years, handmade gins which are also now popular in Europe.

Ivan and Dimple were still working for large companies when they went to a handmade gin tasting one day after work; it was a turning point in their lives. As they approached their 30s, they had been constantly asking themselves how they might challenge themselves to do something different. So, in 2017, they visited a number of small distilleries in the UK, attended distilling workshops and learned from master distillers. On returning to Hong Kong, they resigned their jobs and started their own distillery, as a prelude to launching the first hand-crafted gin produced entirely in Hong Kong.

Compared to other spirits, gin is expressive and can be combined with various spices to tell the rich story of a place. “Every time we develop a new product, I think, ‘What kind of story do we want to tell about Hong Kong?’” says Dimple.

A new distillery after half a century

No one had ever produced gin in Hong Kong before. Starting up the business was a real challenge, and the difficulties came one after another. The first hurdle was the licensing.

Hong Kong law requires a Liquor Manufacturer’s Licence for making spirits containing over 30% alcohol by volume; and behind the licence is a complex taxation regime.

“It’s been a long time since people in Hong Kong have applied for such a licence. The last time was when someone from my grandfather’s generation applied for one - when many distilleries in the New Territories were making Shuang Zheng Jiu (Cantonese rice wine) and Mei Kuei Lu Chiew (Chinese rose wine). But the Customs officers who issued the licences at that time had obviously long since retired,” Ivan says. The modern-day Customs officers were surprised, but took the application seriously. Since autumn 2018, the two partners have been in close contact, understanding the requirements for the design of the factory and the management of raw materials.

After around six months, Ivan finally rented a space and applied for a licence from Customs. The next problem then arose: where to locate the necessary production equipment?

Gin is made in a copper pot still, which is generally not available in Hong Kong; the best are manufactured by long-established European family businesses. So Ivan plucked up courage to contact one of the German companies, Müller; but their response to his email was slow and vague. Desperate for help, Ivan asked a German friend to call the company, and quickly realised that they had serious concerns.

“They had a lot of family meetings to discuss whether to sell us the machine”, continues Ivan. “It turned out that this German company had never heard of anyone in Hong Kong making their own spirit, and was worried that we were ordering the still to copy it and steal their technology”, he laughs.

Eventually, their German friend persuaded the manufacturer that Ivan and Dimple were honest young people who only wanted to make gin.

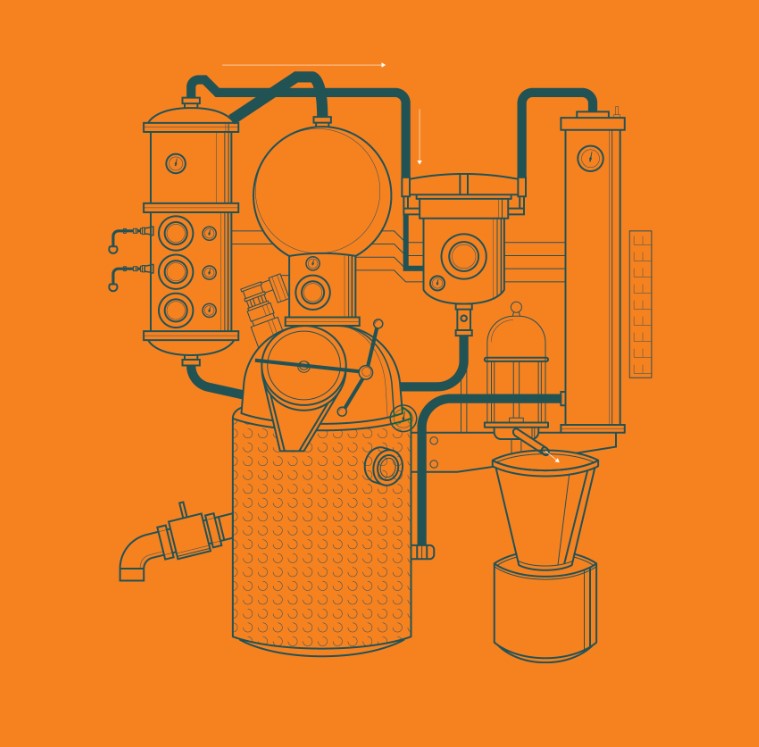

Having worked through various difficulties, in autumn 2019 everything was finally ready. The 2.2 metre high, complex red copper still was shipped from Germany to Hong Kong and assembled. It was a miniature version of the stills found in Europe, specially tailored by Müller to fit the restricted space in Hong Kong. “On seeing the distillation machinery for the first time, we thought it resembled a copper moon, and so we named it ‘Luna’,” adds Ivan.The licence was granted shortly afterwards.

“At that moment, I really wanted to cry because it was finally time to start,” says Dimple. They named their gin distillery “Two Moons Distillery” (Two Moons) — for the moon in the sky, and their own shining Luna in the factory.

“Every time we develop a new product, I think, ‘What kind of story do we want to tell about Hong Kong?”

Gin links two crafts and two generations

The distillery is based in a factory building in Chai Wan but, in contrast to what you might expect from a factory, the atmosphere here is particularly relaxing. The copper pot still and raw materials are housed in a glass room — a bonded area where the freshly-distilled gin has not been taxed. Access to the area is not allowed except for employees. A simple but elegant bar is set up outside the glass room, where visitors can savour gins in the yellow-orange light, while observing the glass bottles containing various spices which hang around the walls.

Dimple explains that gins are made by distillation, a technique invented in ancient Egypt. “Distillation is an amazing process where the liquid is vapourised and sublimated by heating, then cooled quickly and extracted into a spirit; it’s brilliant that the ancients could develop this technique.” Dimple explains that stills are always made of copper because it is a good heat conductor and because the impurities in the alcohol react chemically with the copper, removing them from the liquor.

While the still shipped from Germany was for large scale production, Dimple also needed a medium-sized still for developing new products. Initially they ordered one online, but it was found to be unsatisfactory and needed to be modified.

The art of copper forging also has a long history in Hong Kong. Ivan and Dimple were introduced to Ping Kee Copper Ware (Ping Kee) in Yau Ma Tei — the only hand-made copperware shop in Hong Kong today, dating from the golden age of copperware in Hong Kong.

Ivan and Dimple were hesitant to pay a visit but, to their surprise, the two masters at Ping Kee quickly agreed to help them modify their still. Ivan recounts: “The two masters were in their 80s, didn’t drink alcohol and had never made a still before, but they were open-minded and happy to take on new jobs; we just clicked and it was amazing.”

The most difficult part of producing a still is the curved cooling pipe, and the master was trying to work out how to do this, employing the same techniques used to make coffee kettles’ narrow spouts. Meanwhile the shape of the still’s cooling tower resembled the copper tripods, for storing Chinese herbal tea, that they used to make. “We were inspired by the fact that many of the techniques and crafts are integrated, and that many of the techniques can be adapted and used in a variety of ways,” says Dimple.

The distillation process is just the same, taking in all the different spices. The essential spice for distilling gin is juniper berries, while the rest is left to the free rein of the distiller. Both Dimple and Ivan enjoy cooking Cantonese cuisine, and Two Moons’ first gin incorporates Chinese spices or herbs commonly used in cooking — including sweet apricot kernel, bitter apricot kernel, liquorice root and mandarin orange peel, bringing a taste of the East to the Western spirits.

When they went to pick up the still, they had a bowl of laksa nearby, with its usual Southeast Asian ingredient, Calamansi. “Calamansi has a distinctive aroma and looks like lime. Its unique tangerine flavour makes it perfect for gin. We found out that there are plants in Hong Kong, we sourced them and developed a new product in the still made from Ping Kee. Once we tried the new taste, we fell in love with it.” Dimple recalls.

Giving meaning to “Made in Hong Kong”

There are numerous challenges in developing a manufacturing business in Hong Kong. “There are few raw materials available in Hong Kong, but others have to be airfreighted to Hong Kong, and rents and wages are high.” Ivan says that he and Dimple always reminded themselves that they must be flexible and adaptable on the unknown journey to starting up a business, so as to overcome all the challenges.

But there is always a silver lining, even when the clouds look black. In recent years, Hong Kong consumers have become increasingly supportive of locally-produced products, and the drinks industry has witnessed a boom in home-brewed beer, as well as other Hong Kong-distilled brand of gin alongside Two Moons. Many people are happy to give these new products a try.

Ivan believes that to carry the label “Made in Hong Kong”, they must strive for excellence and be extra strict with themselves: “‘Made in Hong Kong’ does not represent everything; first of all, we must guarantee providing high quality, pure and unadulterated products, and then we have to keep innovating.”

Soon after opening, Two Moons was hit by the unprecedented pandemic of the century. In the summer of 2020, Hong Kong was in the grip of a recession, and the catering industry was in a particularly gloomy state. But the new distillery actively expanded its online sales channels and worked with bar owners to think about what they could do.

“I was reminded of the Five Flower Tea (Chinese herbal tea that consists of five sorts flower) that my grandmother used to make for me. Its flavour is very familiar to Hong Kong people, which is comforting and calming, and we wanted to incorporate this flavour into the gin,” Dimple says. Soon after, they launched a special version of gin with a chrysanthemum top note, making it feel like going back to Grandma’s home.

Looking back on her decision to quit her job more than three years ago, Dimple would like to say to her past self, “Well done! I used to be a bit of an introvert and didn’t even want to call suppliers, but now I can handle anything.”

And Ivan says they are always thinking about how to do better, drawing from the East and the West, and he particularly wants to learn from the two masters at Ping Kee: “When I get older, I want to keep this open-minded attitude, keep trying and keep innovating.”

“Made in Hong Kong’ does not represent everything; first of all, we must guarantee providing high quality, pure and unadulterated products, and then we have to keep innovating.”

Still facing challenges at 80

The afternoon he saw two young business people walk into his ground floor shop on Hamilton Street, Yau Ma Tei, Luk Shu-choi (Luk), who is now 86 years old, knew that he was facing another challenge.

The young pair explained that they needed to modify a still, which of course was not a problem for the master. For more than 60 years, Luk and his younger brother Luk Keung-choi had been working copper with a variety of hammers to create a wide range of products — from household rice pots and water pots for Chinese restaurants, to special commissions such as prop weapons for television dramas, and the large gongs for Sha Tin Racecourse in Hong Kong.

“Some copperware is really difficult to make. One customer asked us to make a piece of pipe for their car, another asked for a lampshade for a vintage car. They are challenges, but if you’re interested in the work it’s a lot of fun to turn what the customer wants into a reality,” Luk says with a smile. He wears a white T-shirt casually, and his hands are toughened from decades of work.

Luk and his younger brother have relied on their hands to support the family’s long-established shop, Ping Kee Copper Ware (Ping Kee) — over eighty years old, and the only copperware shop in Hong Kong today.

One worn-out cotton coat for all

Back in the 1940s and 1950s in Hong Kong, there were 20 to 30 copperware shops like Ping Kee’s, mostly located in Kowloon West. It was the golden age of copperware, when every household used copper water ladles and rice pots, and restaurants boiled water for tea using copperware. Hong Kong copperware shops not only served the local market, but also exported to the United States and other places.

Plastic and stainless steel were not available at the time, and most cooking was done over a wood fire. The copper was easy to hammer into different shapes and heated up quickly when exposed to fire, making it easy to use. In 1940, Luk Ping, who had come to Hong Kong from the Guangdong countryside in Mainland China, set up a copperware shop in a wooden cottage in Lei Cheng Uk Estate (a public housing estate). Later on, the business prospered and the copperware shop moved first to Battery Street, Jordan, and then to Hamilton Street.

Luk recalls that his father, Luk Ping, learned to make copperware from a master only after he settled in Hong Kong. “At that time, the elderly said that a craft was like having a ‘worn-out cotton coat’, which would not make you rich, but could make you a living.” With this “worn-out cotton coat”, Luk Ping’s business flourished, employing nearly ten workers in both retail and wholesale work, supporting his ten children — of whom Luk Shu-choi was the eldest and Luk Keung-choi the third oldest.

In the 1950s, the two brothers graduated from primary school and went to the shop to learn from their father. They had to start with basic chores and perform these well before they were allowed to touch the copper pieces. They had to be trained for at least four years: “There were also several other apprentices in the shop. My father was a very strict teacher to all of his apprentices, with no exception even though I was his son,” Luk says.

The easiest task in copperwork was making water ladles: this required cutting the copper, forming it into a cylinder, adding the flat base, burnishing the joint, adding the long handle and finally rounding off all the parts with a hammer. This is all easy because there are no complex shapes involved. But if you want to make a long, thin, curved teapot spout, or a shrimp-shaped pot handle, that’s an entirely different level of work for the coppersmith.

Luk says he was not cut out for study back then, but he loved to learn how to make copperware. The joy of making it is, in his opinion, to constantly take on new challenges, to sketch out what the customer wants, to test it out and finally to make it to the exact dimensions the customer wants.

“Back in the 1940s and 1950s in Hong Kong, it was the golden age of copperware, when every household used copper water ladles and rice pots, and restaurants boiled water for tea using copperware.”

Diversifying in a changing world

As the years passed, people’s needs also changed. New materials such as plastic, aluminum and stainless steel became popular, electricity became more accessible, mechanised production went mainstream, Chinese restaurants gradually switched to using stainless steel kettles, and copper rice pots for household use were replaced with electric rice cookers.

The two brothers have been in charge of the shop since the 1970s, with the elder brother focusing on drawing, design and market development, and the younger one on the actual copper working.

“I’m the leader,” says Luk, “so of course I have to keep up with the trends and do whatever is popular. I enjoy following the changes in the market, which are a challenge. The customers make strange requests, and if you can deliver and please them, it is really satisfying,” Luk says.

After the decline of both household and catering copperware, Ping Kee turned to making prop weapons for the martial arts and film industries from the 1970s onwards. “We made all the weapons, such as military forks and guandaos (a type of Chinese pole weapon), for the famous TV series ‘The Book and the Sword’. The Hong Kong martial arts community was flourishing at the time, thanks to the influence of Bruce Lee,” Luk recalls. They also seized the opportunity to export copperware to Singapore, mainly to mines.

“In Singapore, when many workers laboured in the mines, they took our copper pots with them to cook rice. Let me sketch one out for you,” Luk explains enthusiastically, as he looks back on his business of years gone by.

But all too soon, the ever-changing tide turned. With the reform and opening up of Mainland China, Hong Kong people went north to set up factories, and the manufacturing industry there became so prosperous and its products relatively inexpensive that the Hong Kong film and television industry began ordering their props from the Mainland instead.

“With free trade, things became cheaper on the Mainland, and we couldn’t even cover our costs selling them at that price, so how could we survive?” Luk asks. But one door closes and another one opens: since the 1980s, more and more herbal tea shops have opened in Hong Kong, and the Luk brothers turned to making copper tripods half the height of a man, for storing herbal tea for those shops; many herbal tea chains became their customers.

Over many years of seizing business opportunities and making copperware for a variety of purposes, the two brothers have always relied on their hands and a selection of hammers. The only electrical appliances used are welding tools and electric drills. Walking into Ping Kee today, you see dozens of hammers scattered around, and almost every one with a different shape and size of head.

“This is the ‘nesting hammer’”, explains Luk, “which is used to make a nest out of copper; this is the ‘sliding hammer’, which rounds out the finished product; and this is the ‘pecking hammer’, which creates a grainy pattern on the final product.” He says there is no need to memorise everything: once the craftsman has mastered the art, he can select the most suitable tool by instinct.

“The easiest task in copperwork was making water ladles: this required cutting the copper, forming it into a cylinder, adding the flat base, burnishing the joint, adding the long handle and finally rounding off all the parts with a hammer. ”

Tied to their craft

For the past decade or so, Hong Kong’s herbal tea shops have been in a slump, and those that are still in business no longer place tea in copper tripods; herbal tea is now pre-bottled and taken away as soon as customers pay for it, for the convenience of fast-moving city dwellers.

“There’s still a copper tripod not far away, but it’s just for decoration, not really in use any more,” Luk says with a sad smile.

As time rolls on, machines have replaced craftsmanship and new materials have been substituted for copper - and so the industry is almost dying out in Hong Kong, say the brothers. As their peers gradually closed down, Ping Kee became the only remaining hand-made copper shop. Now, they don’t employ staff any more.

“Copper, though, is not easy to preserve, as it is prone to oxidation; but it is still valued for its ability to transmit heat quickly,” Luk continues. In recent years, he has been making coffee kettle for cafes and copper congee pots for congee shops. Some congee shops in Hong Kong still only use copper pots to cook raw fish congee, as it boils quickly and keeps the fish tender.

“We don’t make copperware for anyone in particular on a regular basis these days, but as a long-standing shop that’s been here for decades, we always have customers approaching us, like the young people who asked us to modify their still.” Luk says the brothers experimented several times to make that still’s curved cooling pipes. Previously, they had also made a beer-brewing machine for a local craft brewery in Hong Kong.

“You have to be dedicated to your profession. You will understand everything by understanding the underlying principle. If you are interested, you can figure out a lot of things,” says Luk.

The two brothers still open their shop and start working every morning at nine o’clock. On this sweltering September afternoon, the younger brother makes a cup of coffee to refresh himself, while the older brother has bought a cup of milk tea and an egg tart. The plaque left by their father — “Ping Kee Copper Ware” — still hangs high above after more than 80 years.

A few years ago, the two brothers started to think about when they might retire; but, in the end, they can't stop work. “I’m still tied to this craft, and I can’t let go of it…I can’t let go of it...” Luk murmurs. If there really is no way to let go, then he’ll just go with the flow and live for the moment, he decides.

Meanwhile, the two brothers look forward to the next young visitors walking into their old shop.

“There is no need to memorise everything: once the craftsman has mastered the art, he can select the most suitable tool by instinct.”